Reflective practice in the training and continuing professional development of CBT practitioners

Reflective practice in the training and continuing professional development of CBT practitioners

The High Intensity Training Handbook (Clinical Education Development and Research [CEDAR], 2020a) states that:

“Reflective practice has long been recognised as a key component in skills development in professional training. Trainees will complete and submit a number of assessed pieces of reflective writing based on the application of CBT techniques to both clients in the workplace and to their own lives” (para. 1).

These submissions include reflective summaries and self-ratings to accompany formative and summative submissions of video recordings of clinical practice, case reports and an assessment and formulation case presentation, and self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) exercises that culminate in an assessed summary of learning from SP/SR.

The author has found it helpful to frame teaching for CBT trainees using the following general definitions of reflective practice:

“A dialogue of thinking and doing through which I become more skilful” (Schön, 1987, p.31)

The “mindful consideration one’s actions, specifically one’s professional actions” and a “challenging, focused and critical assessment of one’s own behaviour as a means towards developing one’s own craftsmanship” (Osterman, 1990, p. 134)

Reflective practice, which is based on the various educational, developmental and experiential learning theories of Dewey, Lewin, Piaget, Borton and Kolb, seeks to integrate experience with reflection and theory with practice in order to lead to:

“greater self-awareness, to the development of new knowledge about professional practice, and to a broader understanding of the problems which confront practitioners” (Osterman, 1990, p. 134)

For many practitioners, becoming a CBT psychotherapist has the feel of a personal vocation as much as a job, but that doesn’t stop aspects of it being routine. As Peters (1991) puts it:

“Work is not always challenging. It can be downright boring at times, even for professionals…Since humans have a need for meaning in their lives, routine work can actually be harmful to one’s health and well-being. Short of changing one’s job, an antidote is to become a reflective practitioner” (p. 89)

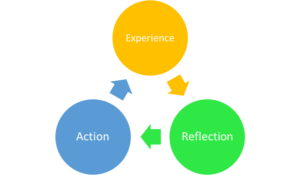

Reflective practice is now articulated in a wide variety of theories and models from outside CBT, including those by Gibbs (1988), Rolfe et al. (2001), Driscoll (2007) and Johns (2009). It is both a commonly employed pedagogical method in diverse training across healthcare professions and beyond, and a method of maintaining and developing professional expertise across the professional lifespan of practitioners. At its most straightforward, reflective practice is the application of a three-phase cycle of experiential learning to professional development. The three phases are: experience, reflection and action, in which reflection on experience guides the choice of subsequent actions that in turn form the basis of new experience (Jasper, 2013: Figure 2).

These phases can be conceptualised in terms of 1) experiential and academic inputs, such as academic teaching, clinical work, and self-experiential or personal practice activities, 2) cognitive-affective reflective processes, such as general reflection and self-reflection in addition to critical and creative thinking, and 3) professional competence outputs as assessed in terms of demonstrable proficiency in the approach being studied. Proficiency might be measured in a number of ways, such as meeting course criteria in order to complete training and gain accreditation, increased self-reflective awareness, or the metacompetence of using reflection to deal with diverse, sometimes poorly defined, problems in professional practice.

It is the author’s experience that initially many trainees either are not convinced of the usefulness of reflection or lack confidence in their ability to reflect and thus to develop a reflective practice. The author has found it helpful when presenting a rationale for reflective practice, to invite trainees to consider the alternative of a non-reflective practitioner, in other words, to consider what it would mean not to reflect and simply to approach psychotherapy as a technical-rational process of applying general and specific practice rules to clearly identified problems. Haarhoff & Thwaites (2015a) provide an illustrative example in the form of an anecdote in which a CBT colleague asked one of the two authors “Why should therapists reflect? Plumbers don’t need to reflect” (p. 1, italics in original). As Haarhoff and Thwaites point out, in fact plumbers do need to reflect in order to learn from experience and solve problems they encounter in practice. They might also benefit from sober self-reflection if a lack of awareness about the impact of their interpersonal behaviours leads to repeated problems with their customers.

We might ask whether the use of a plumber is an appropriate metaphor for a psychotherapeutic approach such as CBT given that it supposes that psychotherapy is essentially a mechanistic, rational process of “re-plumbing” the dysfunctional cognitive “pipes” of the mind to make sure that rational thoughts flow down the correct conduits. Along with the relevant technical and conceptual knowledge that a plumber has, their tools are found in a literal toolbox. A psychotherapist, even in CBT, might have a metaphorical toolbox of techniques, or clinical interventions, but in practice relies on interpersonal understanding and influence through the intentional use of self in relationship to help facilitate cognitive, affective, behavioural and situational change. In fact, on reflection, the unreflective nature of a statement such as “Why should therapists reflect? Plumbers don’t need to reflect” almost makes the case for reflective practice by itself.

Mezirow (1997) frames the choice between a reflective and a non-reflective approach to what is being learned in terms of moral responsibility, that is as one of choosing between, on the one hand, acting uncritically on the received ideas and judgments of authority figures or, on the other hand, learning to “become a socially responsible autonomous thinker” (p. 8) i.e., someone who is capable of using their own insight and judgement in situations of uncertainty. This is perhaps stating the choice more dichotomously than is necessary. As Schön (1983) points out, much of the time we can apply standard practice rules without too much difficulty. On the other hand, it is also undeniably the case that people frequently fail to monitor, and thus pick up, characteristic errors in judgement. In fact, as Stanovich and West (2000) summarise it:

“people assess probabilities incorrectly, they display confirmation bias, they test hypotheses inefficiently, they violate the axioms of utility theory, they do not properly calibrate degrees of belief, they overproject their own opinions on others, they allow prior knowledge to become implicated in deductive reasoning, and they display numerous other information processing biases” (p. 645).

Perhaps it would be more useful to frame the distinction between reflective and non-reflective approaches in terms of cognitive processing styles. Errors in judgement based on, for example, the application of standard practice rules in a non-reflective manner, reflect the use of intuition or heuristics that have been labelled System 1 cognitive processes. System 1 processes are fast, automatic, perceived as effortless, work by association, and are often emotionally charged. They tend to be governed by habit and can therefore be difficult to control or modify. What we think of as reasoning, or System 2 cognitive processes, on the other hand, is a slower, more effortful, deliberately controlled, serial process (i.e. processing one idea at a time) that is relatively flexible and potentially rule-governed. An important corollary to this distinction is that System 2 monitors System 1 (Kahneman, 2003), helping us to understand why the perceptions, behaviour, cognitions and affects that constitute experience form the raw material that the slower, more effortful process of deliberate reflection operates on in order to make meaning from experience and correct initial impressions or unhelpful responses.

There is also a reflexive element (in the sense of turning back on itself) to reflective practice that acknowledges that our development as professionals might in some senses mirror the psychotherapeutic process as it is understood in CBT. The idea of teaching the client to become their own therapist is foundational in CBT theory and practice (Beck, 2011). If reflective practice can be seen as a form of experiential learning with the goal of becoming more skilful, then CBT itself has been formulated as experiential learning (Milne et al., 2001) Drawing explicitly on Kolb’s (1984) development of the Lewin experiential learning model, Milne et al. state that:

“in effective therapy patients will tend to reflect on their situation, engage in new experiences (including behaving in alternative ways), engage in problem solving and coping strategies, and finally develop alternative theories and concepts of their world…true accommodation will occur when the information processed leads to a new construction of the world” (p. 23).

If, as Milne et al. (2001) propose, CBT is a form of psychotherapy that is in key aspects analogous to experiential learning, then a reflexive personal appreciation of the process of experiential learning becomes a potentially important therapeutic capacity. By reflexive appreciation, the author means that practitioners are able to make links between their own experiences of learning and those that their clients may be experiencing. Training in psychotherapy can be both professionally and personally transformative, and an ongoing reflective practice might help to integrate learning that is taking place at a number of different personal and professional levels of lived experience. Self-reflection on these transformative personal experiences might alert practitioners to salient aspects of the client’s experience, in order to deliver therapeutic interventions sensitively and effectively.

Reflective practice is highly valued in the High Intensity CBT training at the University of Exeter, in line with other similar training courses. CBT trainees are exposed to a wide range of teaching inputs, including lectures, clinical skills tutorials, supervised clinical practice, clinical supervision and SP/SR activities. They are required to demonstrate their developing competence academically, in terms of practice skills, and in terms of reflective practice through writing essays and case reports, participation in supervision, submission of recordings of clinical practice, and writing reflective summaries of both clinical recordings and of SP/SR activities. At the conclusion of their training, it is hoped and intended that they will display competences aligned to the core curriculum of the British Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapy (BABCP) (Hool, 2010), the Roth and Pilling (2007) CBT competence framework, and the IAPT High Intensity Curriculum (Liness & Muston, 2019). The BABCP core curriculum summarises the required learning outcomes of training as:

- “A critical understanding of the scientific and theoretical underpinnings of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies for common mental health disorders across the specialisms

- The core clinical competences required to practise CBT with common mental health disorders across the specialisms” (Hool, 2010, p. 5).

Roth & Pilling (2007) distinguish five areas of clinical competence in the practice of CBT:

- Generic competences – as used in all psychological therapies

- Basic cognitive and behavioural therapy competences – as used in both low- and high-intensity interventions

- Specific cognitive and behavioural therapy techniques – the core technical interventions employed in most forms of CBT

- Problem-specific competences – the packages of CBT interventions for specific low and high-intensity interventions

- Metacompetences – overarching, higher-order competences which practitioners need to use to guide the implementation of any intervention

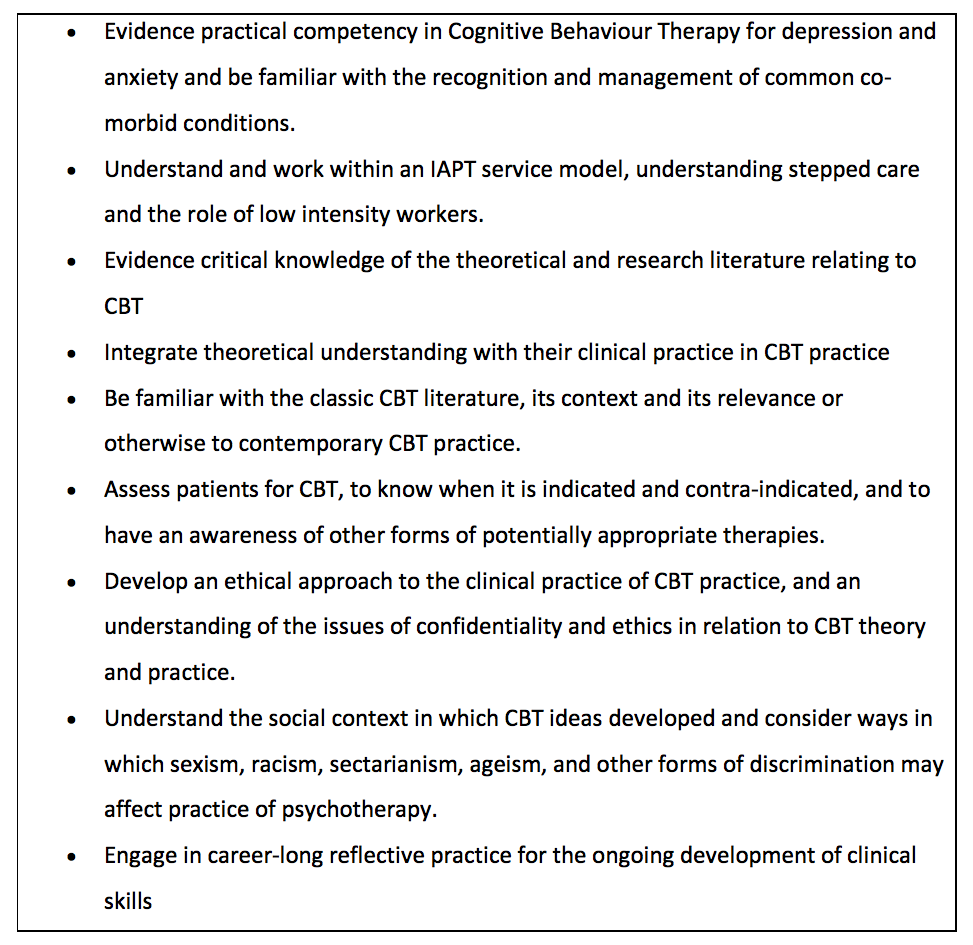

The specific programme aims of the University of Exeter PG Dip in High Intensity Psychological Therapy (CEDAR, 2020b: Box 1) seeks to provide trainees with “all the necessary academic and training requirements to meet BABCP accreditation as a cognitive behavioural therapist” (para. 1) including the ability to “engage in career-long reflective practice for the ongoing development of clinical skills” (para. 2).

Box 1: Specific programme aims for the University of Exeter’s PG Dip in High Intensity Psychological Therapy (CEDAR, 2020b).

The need for reflective practice does not end at completion of formal training, which is more a rite of passage and validation of one’s baseline competence than the completion of a longer professional journey towards proficiency. As we have seen, the goal of the training is, in part, to inculcate a career-long engagement with reflective practice because professional skill development is a lifelong process (Osterman, 1990). The need to update one’s knowledge and skills in order to develop professionally are part of the rationale for undertaking continuing professional development (CPD) activities, whatever one’s level of experience or qualifications in CBT. The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP, 2020) requires accredited practitioners to engage in “a minimum of five CBT CPD activities per year…This must include at least six hours of CBT skills workshop(s) each year” (para. 1).

As well as keeping a record of CPD, practitioners are required to complete a reflective statement for each activity, where practitioners demonstrate that they have reflected on how the activity was relevant to their clinical practice, what they learned, and how it will impact on their practice. There is evidence that when participants were asked to complete a reflection worksheet at the end of each day of a 2-day skills workshop, and again following an email reminder at 1, 4, and 8 weeks after the training, that this led to a greater awareness and use of skills than those in a control group who did not complete these reflective writing tasks (Bennett-Levy & Padesky, 2014).

Reflective practice also appears to be a key component in developing and maintaining professional expertise among therapists drawn from a diverse range of therapeutic modalities. For example, Jennings and Skovholt (1999) reported that a selection of peer-nominated “master therapists” displayed the following characteristics that are either by their nature reflective or plausible consequences of reflective practice. Master therapists:

“(a) are voracious learners; (b) draw heavily on accumulated experiences; (c) value cognitive complexity and ambiguity; (d) are emotionally receptive; (e) are mentally healthy and mature and attend to their own emotional well-being; (f) are aware of how their emotional health impacts their work; (g) possess strong relationship skills; (h) believe in the working alliance; and (i) are experts at using their exceptional relational skills in therapy” (p. 3)

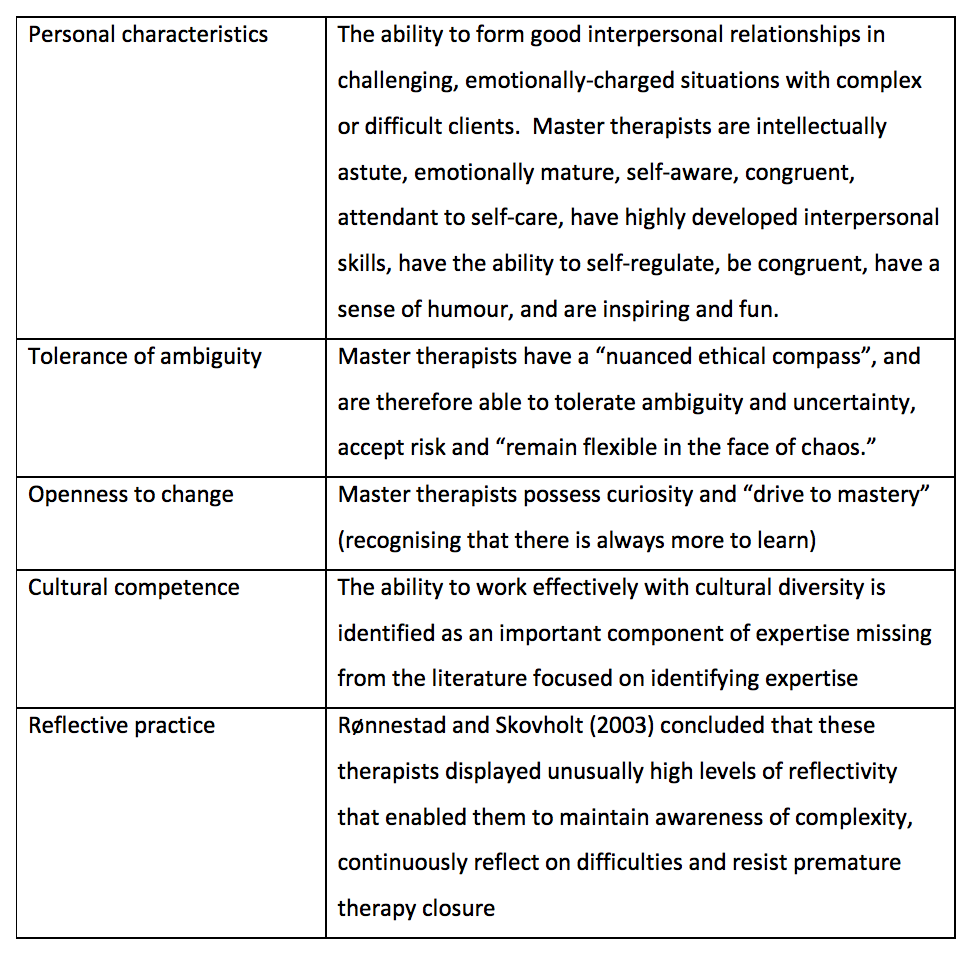

In a later review of the literature on the development of expertise in therapists, Jennings et al. (2003) attempted to differentiate between experienced therapists and those that demonstrate expertise, whatever their level of experience, given that experience alone is not an adequate explanation for differences between therapists in their clinical outcomes with clients. Where experience did contribute to expertise it was in the ability to conceptualise clients at a broader, more abstract and inclusive level in order to make more sophisticated critical judgements. Expert therapists had a range of personal characteristics including a number that appeared paradoxical, such as both a drive to mastery and a sense of never having fully arrived. Words that were used to describe these expert therapists included: congruent, intense, open, curious, reflective, self-aware, generous, analytic, fun, inspiring, and passionate. Some of the identifying characteristics included: self-acceptance, the use of complex metaphorical descriptions of human life, and having internalised thousands of hours of practice. Other characteristics included: embracing ambiguity, humility and a will to grow, boundaried generosity, and a welcome openness to feedback from life. Again, these appear to be attributes that one would naturally associate with highly reflective practitioners and have been summarised by Haarhoff & Thwaites (2015b) in their chapter on reflection in CBT (Table 1), where they also include the importance of cultural competence.

Table 1: characteristics of master therapists, Jennings et al., 2003, adapted by Haarhoff & Thwaites, 2015b)

In a similar vein, Wampold and Carlson (2011) identified comparable qualities and actions of effective therapists that again appeared conceptually related to the capacity and willingness to engage in reflective practice. Effective therapists were seen to:

- Have sophisticated interpersonal skills

- Provide an acceptable and adaptive explanation for the client’s distress (i.e., a credible formulation)

- Provide a treatment plan that is consistent with the explanation provided to the client

- Be influential, persuasive, and convincing to promote in the client hope in the treatment’s effectiveness and expectations of progress

- Continually monitor client progress in an authentic way (I.e. communicate that they genuinely want to know how well the client is doing)

- Be flexible and will adjust therapy if resistance to the treatment is apparent or the client is not making adequate progress

- Not avoid difficult material in therapy and use such difficulties therapeutically

- Communicate hope and optimism, and is able to help clients mobilise their resources

- Be aware of the client’s characteristics (class, ethnicity, sexual orientation etc.) and context (for example, level of support at home) and how the therapist’s characteristics interact with the client’s

- Be aware of their own psychological process and do not inject their own material into the therapy process (for example, countertransference) unless such actions are deliberate and therapeutic

- Be aware of the best research evidence related to the particular client, in terms of treatment, problems, social context, and so forth

- Seek continually to improve their skills, knowledge, qualifications and experience

Dlugos & Friedlander (2001) used a qualitative methodology to identify the qualities and activities of experienced therapists that maintained a “passionate commitment” to their work and were able to avoid burnout. These therapists were found to:

- Be effective in creating boundaries between their professional and nonprofessional life,

- able to use leisure activities to provide relief from stress,

- see professional obstacles as challenges to be overcome,

- have a range of diverse activities that provided freshness and energy,

- frequently seek feedback and supervision,

- take on social responsibilities, and

- experience a strong sense of spirituality.

These qualities seem related to, if not contingent on, lifelong engagement with reflective practice; at the very least, reflective practice seems implicit in these descriptions.

There is a potentially beneficial reciprocal relationship between the engagement with one’s professional activities as opportunities for learning, as in reflective practice, and the capacity for learning that Dweck (2013) describes as a growth mindset. A growth mindset is the belief that intellectual abilities and other personal characteristics can be developed. It tends towards a greater focus on developing one’s ability and the use of a questioning strategy, or efforts to correct and learn, after failure. A fixed mindset holds that one’s personal characteristics are immutable. As a consequence, a fixed mindset tends towards a greater focus on validating one’s ability and towards drawing negative conclusions about one’s ability after struggle or failure (Yeager & Dweck, 2020). There is evidence that a growth mindset in professional helpers is beneficial in a number of ways. If one thinks of clients as having the capacity to learn and develop, it predicts that the practitioner will have greater work engagement (characterised by vigour, dedication and absorption). If one has a growth mindset towards oneself as a professional, that predicts both work engagement and self-rated performance (Visser, 2013). In so far as a willingness to reflect (and self-reflect) and a growth mindset are mutually reinforcing, this suggests that purposeful and intentional reflective practice is a key pathway to maintaining professional and personal satisfaction. Making time to think about what makes a good therapist, what we do well, why this work is meaningful to us, and where we can develop our knowledge and skills, can be useful questions to help us track our current state of wellbeing and fitness to practice as well as our professional progress. Encouraging a growth mindset in trainees so that they are able to move from fixed self-theories about their strengths and weaknesses to developing mastery in the face of challenges, might help empower trainees who are not yet confident in their ability to engage with reflective practice (Osman et al., 2020).

Methods of reflective practice across different professional training may be diverse. Kottkamp (1990) describes the following “catalogue of means” of reflective practice (p. 184):

- reflective writing,

- reflective journals,

- writing case records,

- contrived situations (e.g. role play, case studies and simulations),

- instrument feedback (e.g. from questionnaires),

- electronic feedback (e.g. video and audio recordings of clinical practice),

- metaphor (as a method for clarifying personal understanding),

- constructing a (metaphorical) platform (a personal statement of one’s espoused theory in order to detect discrepancies with one’s theory-in action), and,

- shadowing and reflective interviewing.

In psychotherapy generally, personal therapy is often undertaken and even mandated as a reflective exercise to increase self-awareness, although generally not in training in CBT in English-speaking countries (Haarhoff and Thwaites, 2015). In increasing numbers of training courses, as at the University of Exeter, the structured practice of CBT skills and techniques on oneself using Self-practice/Self-reflection (SP/SR) is now being used to enhance therapist skills and understanding. Therapy-specific methods of reflection as part of reflective practice will be discussed in more detail in the section on self-reflective awareness.

In summary, reflective practice involves the process of reflection, that is mindful consideration of one’s actions; it is an active process, involving a dialogue between thinking and doing; it is purposeful as it is intended to help us become more skilful; it is cyclical in that the more experience we have, the more there is to reflect on and learn from and the more skilful our actions become; and it is lifelong in so far as we will always seek to improve our knowledge, skills, professional understanding and personal self-awareness.

Part 2: Models of experiential, transformative, and emancipatory learning

Photo by Dawid Zawiła on Unsplash