The reflective practitioner – reflection and self-reflection as a skill

The reflective practitioner – reflection and self-reflection as a skill

The work of John Dewey has been highly influential on models of experiential learning and the process of reflection or, as it is sometimes called, reflective thinking, as has already been touched on. Dewey stated that reflective thinking consists of “[a]ctive, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends” (Dewey, 1938, cited by Rodgers, 2002, p. 850, italics in original). This definition sounds more like what we might understand as critical thinking in the sense that it is logical, rational and dispassionate. However, while Dewey’s language is not always easy to understand, and his meaning is therefore not always clear, there is more to his thought than dispassionate, individual inquiry. Rodgers, for example, summarises Dewey’s four criteria for reflection as follows:

- “Reflection is a meaning-making process that moves a learner from one experience into the next with deeper understanding of its relationships with and connections to other experiences and ideas. It is the thread that makes continuity of learning possible, and ensures the progress of the individual and, ultimately, society. It is a means to essentially moral ends.

- Reflection is a systematic, rigorous, disciplined way of thinking, with its roots in scientific inquiry.

- Reflection needs to happen in community, in interaction with others.

- Reflection requires attitudes that value the personal and intellectual growth of oneself and of others” (p. 845).

Dewey’s four criteria considerably extend the idea of reflection from critical thinking, situating it in both the person doing the reflecting and the interactional method and prosocial purposes behind it as an intellectual activity. The modern conceptualisation of reflective thinking, while having its origins in Dewey’s work, narrows the focus of reflective thinking to its role in developing professional flexibility. It can be traced to the concept of the reflective practitioner in the work of Donald Schön (1983, 1987), which itself came from a decade of research by Argyris and Schön into the dynamics of effective leadership (Osterman, 2010).

Schön was interested in the development of practitioner skill and competence as a form of professional artistry that goes beyond practices as they are taught. The concept of the reflective practitioner therefore refers to a professional who uses their experience to develop more effective action strategies. Schön (1988) argued that reflective practitioners first learn to recognise and apply standard practice rules and techniques, then, when confronted by problematic cases where those rules and techniques prove inadequate, develop and test new forms of understanding and action. He described how practitioners have to move from the “high hard ground” of simple technical problems of practice to the “swampy lowlands” of real-world practice in which they have to tackle poorly structured problems. Schön (1987) described it as follows:

“Because the unique case falls outside the categories of existing theory and technique, the practitioner cannot treat it as an instrumental problem to be solved by applying one of the rules in her store of professional knowledge. The case is not ‘in the book’. If she is to deal with it competently, she must do so by a kind of improvisation, inventing and testing in the situation strategies of her own devising.” (p. 5)

The phrase “store of conceptual knowledge” may refer to explicit or implicit knowledge. The latter is what Schön describes as knowing-in-action, that is, a form of tacit knowledge that practitioners use in their everyday work. Being tacit, it is not codified and therefore it can be difficult for practitioners to articulate the artistry that lies behind much of their professional activity. Yet, Schön argues, it is vital to do so in order to understand “theories-in-use”, that is, the assumptions, values, and personal and professional philosophy that are implied by the skilled performance of a professional role. Theories-in-use may be different from the practitioner’s espoused theory, in other words, the practitioner’s ostensible explanation of why they do what they do. This can lead to contradictions between the reasons people give for their behaviour and the actions they take. Argyris and Schön (1974) wondered whether one of the reasons people have difficulty in learning new theories is not that the theories are necessarily difficult to understand, but that they contradict the theories-in-use that are currently employed to guide practice. It is undeniably unsettling to have one’s assumptions challenged; the problem of practitioners feeling deskilled makes the teaching and acquisition of new knowledge and skills a potentially fraught process. In challenging circumstances, there remains a temptation to revert to a former way of knowing and acting that is associated with a more confident and competent professional identity. However, there is no way of avoiding the fact that some former knowledge and beliefs may have to be profoundly modified in order to make progress in developing a new professional identity. Reflective practice may be one way to make easier the process of assimilating a new body of knowledge and stretching one’s assumptive world to accommodate new ways of knowing and acting.

For example, in terms of CBT practice, an espoused theory might be that clients learn best when they come to their own conclusions, therefore guided discovery is the most effective route to meaningful cognitive change. However, perhaps as a consequence of a former, more directive approach that is identified with a previous professional identity, the trainee’s theory-in-use might be reflect a different reality. For example, that there is simply no time to explore the client’s assumptive world, or that there will be negative consequences for the practitioner if sessions take too long or if the client’s scores do not improve as rapidly as the organisation expects them to. These factors might therefore lead to a practice that looks considerably more didactic than would be expected on the basis of espoused theory. This discrepancy might only be highlighted when reflecting in supervision, for example on homework non-compliance, when it becomes clear that the client doesn’t experience a great deal of agency in devising and setting tasks that help them to take ownership of both the problem and its solution. Making the transition from didactic practice to guided discovery as a theory-in-use will need to be handled sensitively in order not to elicit either avoidance of bringing sensitive material for consultation, or feelings of shame and discouragement. As Peters (1991) points out, reflection is not necessarily comfortable for the practitioner as it involves being open to “a scrutiny of beliefs, values, and feelings that may be strongly held and about which there is great sensitivity” (p 95). It might also be important to note that, despite best intentions, the real-world conditions under which people have to practice often force us as practitioners to make uncomfortable compromises that we have to resolve as best we can with our beliefs, values and, ultimately, our conscience.

Schön distinguished between two forms of reflection: reflection on action, such as occurs after an event, and reflection in action which occurs as an event is taking place. Kottkamp (1990) refers to these figuratively as offline and online reflection respectively and states that it is not clear whether methods of reflection, such as reflective writing, are necessarily effective in both domains, given that most of the time formal reflection occurs after the event in question. In psychotherapeutic practice, the use of supervision would be an example of reflection on action, for example when reviewing a problematic experience in therapy, whereas reflection in action is the ability to think on one’s feet, for example in managing an unexpected risk of rupture in the therapeutic alliance.

Reflection as a skill

While the term reflection is frequently used to describe an attribute or skill of the reflective practitioner and a component of experiential learning and reflective practice, its definition can be elusive and differs from author to author. Each definition tends to highlight some facets of reflection more than others but they all tend towards similar conclusions that can, for the most part, be found in Dewey’s previously described conditions for reflection. Boud et al. (1985) describe reflection as a response of the learner to experience when pursuing goal-directed intentional learning and thus “a generic term for those intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to new understandings and appreciations” (p. 19), while for Peters (1991) it involves “identifying one’s assumptions and feelings associated with practice, theorizing about how these assumptions and feelings are functionally or dysfunctionally associated with practice, and acting on the basis of the resulting theory of practice” (p. 89).

For other authors, reflection is more simply a conscious awareness of what we are doing and why we think we are doing it (Dallos & Stedmon, 2009), or “critically analysing one’s actions with the goal of improving one’s professional practice” (Imel, 1992, p.2). Osterman (1990) describes it as the essential part of leaning, because it involves making sense of, or extracting meaning from, experience. Specifically, Osterman states that “without reflection, theories of action are not revised and, until new concepts, ideas or theories of action begin to influence behaviour, learning will not occur” (p. 135). For Peters (1991) “”Reflective practice is a special kind of practice. It involves a systematic inquiry into the practice itself, even as the practice is under way” (p. 95).

What seems to be common to all these definitions is that reflection privileges learning for greater understanding, rather than 1) rote learning to develop knowledge by embedding facts into semantic memory, 2) instruction, modelling, imitation and practice to develop procedural skills, 3) so-called “animal learning” i.e. classical and operant conditioning that alter approach/avoid behaviour on the basis of learned associations and/or reward-based contingencies, or 4) simple stochastic learning, that is learning by trial and error. What authors appear to agree on is that learning through reflection is unique in its focus on the development of more abstract generalisations that are applicable to novel contexts and thus help develop behavioural and cognitive flexibility.

Perhaps we might benefit from thinking of the term reflection in relation to other reflecting bodies, such as a mirror or a pool of clear water. A mirror reflects an object, it is not the object itself, just as we reflect on an event or occurrence with some degree of intellectual or emotional distance from the event itself. Reflection is a skill, but it does not stand on it its own. Merriam et al. (2007) point out that, in order to gain genuine knowledge from an experience, the learner must be willing to be actively involved in the experience, be able to reflect on the experience, possess and use analytical skills to conceptualize the experience, and possess decision making and problem-solving skills in order to use the new ideas gained from the experience. The following section describes some of the intellectual skills and environmental conditions that might be needed for effective reflection.

Critical thinking is essential both to academic learning and to reflection if valid conclusions are to be drawn from experience. Cottrell (2017) describes critical thinking as a process that is a “complex process of deliberation which involves a wide range of skills and attitudes” (p. 2). These include:

- identifying other people’s positions, arguments and conclusions

- evaluating the evidence for alternative points of view

- weighing up opposing arguments and evidence fairly

- being able to read between the lines, seeing behind surfaces, and identifying false or unfair assumptions

- recognising techniques used to make certain positions more appealing than others, such as false logic and persuasive devices

- reflecting on issues in a structured way, bringing logic and insight to bear

- drawing conclusions about whether arguments are valid and justifiable, based on good evidence and sensible assumptions

- synthesising information: drawing together your judgements of the evidence, synthesising these to form your own new position

- presenting a point of view in a structured, clear, well-reasoned way that convinces others.

Common barriers to critical thinking include misunderstanding what is meant by criticism and assuming that it means being negative when in fact it is to increase understanding and to improve practice; over-estimating our reasoning abilities and mistaking the ability to ‘win” an argument for the ability to construct a credible analysis or critique of evidence; a lack of cognitive methods, strategies and practice that might require skills training; a reluctance to criticise those with more expertise such that we become overly deferent to perceived authority; emotional reasons as a result of discomfort aroused by challenging deeply held and personally meaningful beliefs; mistaking information or knowledge of facts for the deeper understanding that comes from making judgments; and, insufficient focus and attention to detail, perhaps due to competing demands for time or working memory capacity. For many CBT trainees the intellectual demands of postgraduate training can be somewhat intimidating. It might be useful for them to reflect on the personal challenges they have faced in training in order to gain an appreciation of the challenges their clients may also face in coming to grips with new ways of thinking about themselves and the world. For example, the emotional and intellectual challenges of being able to understand and critique a formulation that is shared with them.

Critical thinking skills depend on the capacity for epistemic cognition, which is the metacogntive capacity to comprehend and articulate one’s beliefs about the limits of what can be known, with what certainty, and by what criteria, but in a way that does not paralyse the practitioner through uncertainty and indecision. Rather than relying on pre-reflective reasoning that relies on received wisdom, or quasi-reflective reasoning that admits to uncertainty but selects information that supports a particular world view (a form of motivated reasoning), the reflective practitioner is capable of employing epistemic reasoning to come to a “most reasonable” judgment based on the available, credible evidence (King & Kitchener, 2002). An approach to CBT as a psychotherapy that employs epistemic cognition might need to recognise, for example, the replication crisis that academic psychology is struggling with (Wiggins & Chrisopherson, 2019), and continuing questions as to which psychotherapies are effective for which conditions and why (Leichsenring et al., 2019), while continuing to recognise the body of evidence foe the effectiveness of treatment approaches. Reflective practice that utilises epistemic reasoning might therefore be key to continuing to maintain a coherent practice in the face of uncertainty while acknowledging both what is known as well as its limitations.

Problem solving of this kind will be familiar territory for many CBT trainees and almost certainly all practitioners, so should present no difficulty conceptually. Applying creative problem solving within the context of problems encountered in professional practice might most easily fall into the stage of experiential learning that is associated with active experimentation, to use Kolb’s term. Creative thinking in practitioners however might be limited by an over-reliance on what has been taught (and therefore is believed to be known absolutely) leading to undue reliance on the “high hard ground” of technical problems and a failure to recognise the inherently uncertain business of working psychotherapeutically, the limitations of the treatment approach, or our limitations as practitioners. As Marsha Linehan (1993) noted that “when patients drop out of therapy, fail to progress, or actually get worse…the therapy, the therapist, or both have failed” (p. 108) because either the therapist failed to deliver the treatment competently or the therapy itself was inadequate for the problems being treated or in motivating or preparing the client to participate effectively in treatment. Creative problem-solving is a way of arriving at strategies both to improve therapy for specific therapeutic problems encountered in practice and the skill of reflection helps to generalise that learning.

Mezirow’s (2009) description of communicative learning as an element of transformative learning requires that participants are able to participate in discourse with others. The optimal conditions for discourse are ones in which learners have accurate and complete information; are free from coercion, distorting self-deception or immobilizing anxiety; are open to alternative points of view; are able to understand, to weigh evidence and to assess arguments objectively; are able to become aware of the context of ideas and critically reflect on assumptions, including their own; have equal opportunity to participate in the various roles of discourse; and, “have a test of validity until new perspectives, evidence or arguments are encountered and validated through discourse as yielding a better judgement” (p. 92). The process of transformative learning involves critical reflection, empirical research (for instrumental learning), free participation in discourse, taking action, and acquiring a disposition to become more critically reflective, to participate in discourse, and to follow through on insights gained (Mezirow, 2009). As part of reflective practice, it might be worthwhile for trainees to consider the extent to which they and their clients have access to those optimal conditions and which aspects of the process of transformative learning are most relevant both to their own learning and to those of the clients they see in clinical practice.

These overlapping approaches to learning could be thought of as part of a process of developing conscious competence, which could be defined as the capacity to articulate both the what and the why of professional activities. The concept is borrowed from Broadwell’s (1969) four stages of competence model, which sought to expand on the idea that teaching is a skill. Broadwell described four types of teachers: the unconsciously incompetent, dull and ineffective teacher, distanced from the learner’s objectives who is unaware of their ineffectiveness; the consciously incompetent teacher who is aware of their limitations and seeks to remedy the situation; the consciously competent teacher who knows not just that they are competent but what makes them competent; and finally the unconsciously competent teacher is who is naturally good at teaching but is not able to articulate what it is that do they and why, of whom Broadwell said, “He’s good, but he doesn’t know what it is that makes him good” (p. 3). The one teaching skill that the unconsciously competent teacher lacked is the self-awareness that would enable them to teach others to teach.

Using Broadwell’s model, we can identify the importance of reflection to develop professional knowledge and self-awareness in order to progress towards conscious competence. If CBT itself is a learning process that teaches the client to become their own therapist, and its practitioners are “teachers” in the broadest sense (i.e. facilitators of learning experiences) then a willingness to seek and learn from feedback is critical to uncovering the blind spots that might make us unconsciously incompetent in order to develop and maintain our conscious competence.

Models of reflective practice

The concepts of reflection, reflective thinking, and experiential learning have given rise to a number of models of reflective practice that all appear to be variations on very similar themes, as previously described. They are derived, in the main, from the work of Borton (1970) and Kolb (1984) and have been applied in a variety of contexts, usually professional healthcare education. The differences between the various models are, it could be argued, relatively trivial compared to the central pedagogical ideas around which they are constructed, i.e. learning through reflection on doing. There follows a brief review of some of the more commonly used reflective practice models.

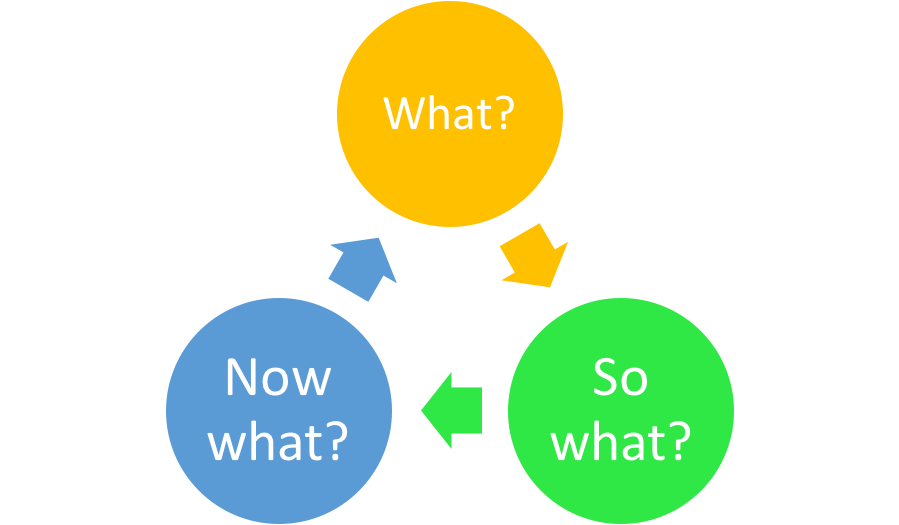

Rolfe et al. (2001) developed a framework for reflective practice in nursing that is explicitly based on Borton’s (1970) model and the colloquial expressions (or sentence stems) that Borton devised to capture the meaning of the three interlinked processes (Figure 4). Rolfe then added a number of cue questions to elaborate the model as a vehicle for inquiry, specifically into nursing practice (Table 2).

Driscoll (2000) also used Borton’s model as a template to reflect on experiences in clinical practice, elaborating each of the three stages (Figure 5).

Driscoll too developed a number of cue questions that are intended to be useful to practitioners when reflecting in supervision (Table 3).

Table 3: Trigger questions associated with the Driscoll (2000) model of reflective practice in clinical supervision

Johns (1995) developed a Model of Structured Reflection that draws on Barbara Carper’s epistemological framework that describes four “ways of knowing”: empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic. For Johns, the “the essential nature of learning through experience is reflexivity” (p. 226), by which he means that practitioners are able to respond to clinical situations having assimilated existing personal knowledge with learning through reflection. Learning to become an effective practitioner involves “personal deconstruction and reconstruction” in a process of enlightenment, empowerment and emancipation, where:

“Enlightenment’ is to understand ‘who I am’ in the context of defining and understanding my practice, ’empowerment’ is to have the courage and commitment to take necessary action to change ‘who I am’, and ’emancipation’ is to liberate myself from previous ways of being to become ‘who I need to be’, as necessary to achieve effective desirable practice” (p.226).

Each domain of knowledge can be elaborated into a set of questions (Table 4) relevant to each of Carper’s “ways of knowing”. The aesthetic domain consists of Intentions and actions; the personal domain of cognitive and affective reactions; the ethical domain of moral considerations of right and wrong, the domain of empirics of semantic knowledge; and the domain of reflexivity consists of a consideration of the implications of experience that synthesises the previous ways of knowing but is future-focused.

Without explicitly drawing on Kolb’s work, Peters (1991) developed a model using the acronym DATA (standing for describe, analyse, theorise, act) that is virtually identical to Kolb’s use of the Lewin experiential learning model. Peters describes four steps to reflective practice, as follows:

- “Describe the problem, task, or incident that represents some critical aspect of practice needing examination and possible change.

- Analyse the nature of what is described, including the assumptions that support the actions taken to solve the problem, task, or incident.

- Theorise about alternative ways to approach the problem, task, or incident.

- Act on the basis of the theory” (p. 91).

Peters (1991) states that while reflective practice might not always be a comfortable or pleasant experience, it is likely to be rewarding in terms of one’s professional development and in providing a “better service to others” (p. 95). It might also serve as an antidote to the dangers of becoming bored with some of the routine aspects of work that fail to challenge practitioners and to inject personal meaning into work.

Pfeiffer and Jones (1975) extended the model described by Kolb (1984) by adding a fifth, stage that they describe as “sharing” (Figure 6). The use of blogs to share reflections is an increasingly common device in training to enhance learning, especially in self-experiential activities such as self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR). Focus group-based research suggested that, despite technical difficulties, blogs enhanced SP/SR, established a learning community, and improved course supervision (Farrand et al., 2010). In general, trainees are encouraged in their public blog entries to focus on the process of reflecting, rather than disclosing potentially sensitive personal content. However, in the author’s experience, it can be helpful to contextualise one’s reflections on process with a level of disclosure on content that feels safe enough to communicate to fellow trainees, especially if these works are not being assessed. In reflecting on role plays or clinical practice, the importance of sharing the content of experience (what was thought, felt or done during an experience) is also potentially helpful, and is less likely to be of a personally sensitive nature than self-experiential exercises.

Two additional models of reflection also increase the number of steps involved. Gibbs’ (1988) model has six steps with corresponding questions for reflection comprising: 1) description: what happened?; 2) feelings: what were you thinking and feeling?; 3) evaluation: what was good and bad about the experience?; 4) analysis: what sense can you make of the situation?; 5) conclusion: what else could you have done?; and, 6) action plan: if the situation arose again, what would you do?

Gibbs’ model has proved popular over the years but has been criticised for not being easy to recall in practice and because some of the stages are unclear and appear to repeat each other. As a consequence, Barksby et al. (2015) developed a seven-stage process of reflection using the acronym REFLECT that they argued was easier to recall in practice, while maintaining the benefits of a structured model. It has the benefit of specifying a timescale for action, which brings the model in line with the SMART model of operationalising therapy goals that is often taught in CBT (e.g. Kennerley et al., 2016). The seven stages are:

- R – RECALL the events (stage 1): Give a brief overview of the situation upon which you are reflecting. This should consist of the facts – a description of what happened

- E – EXAMINE your responses (stage 2) Discuss your thoughts and actions at the time

- of the incident upon which you are reflecting

- F – Acknowledge FEELINGS (stage 3) Highlight any feelings you experienced at the time of the situation upon which you are reflecting

- L – LEARN from the experience (stage 4) Highlight what you have learned from the

- situation

E – EXPLORE options (stage 5) Discuss options for the future if you were to encounter a similar situation - C – CREATE a plan of action (stage 6) Create a plan for the future – this can be for

- future theoretical learning or action

- T – Set TIMESCALE (stage 7) Set a time by which the plan outlined in stage 6 will be complete (Barksby et al., 2015, p. 22)

In addition to these models, Bennett-Levy, Thwaites et al. (2009) have proposed a series of reflective questions that can provide a template for reflection. They consist of the following steps:

- Observe the experience (e.g. how did I feel, what did I notice?)

- Clarify the experience (e.g. was it helpful, what did not change?)

- Implications of the experience for clinical practice (e.g. for one-to- one therapy, for supervision and consultation, etc.)

- Implications of the experience for how I see myself as ‘person of the therapist’ and/or ‘self as therapist’.

- Implications of this experience for my understanding of cognitive therapy and theory.

In summary, the concept of the reflective practitioner as one who is able to respond flexibly to the unexpected in practice has proved a remarkably enduring one in terms of both the art and artistry of professional practice in diverse fields. Models of reflective practice that are closely tied to models of experiential learning provide a structure for reflection that can enhance reflective practice. That said, there are some pros and cons to using a structured model to reflect. A structured approach offers a useful starting point for practitioners who are starting out with reflective practice by breaking down situations for reflection into more manageable constituent parts. Having a clearly defined beginning and end to the situation on which the person is reflecting allows practitioners to know when the process of reflection is complete, for example when an action plan has been devised. It might also be argued that using a structured approach to reflection corresponds well to the practice of CBT as a structured psychotherapy whose therapeutic process is analogous to experiential learning. CBT practitioners frequently make use of exercises that involve writing such as monitoring (e.g. diaries) or in engaging with the meaning of experience, or through using diagrams to explain a formulation. On the other hand, using a model as a basis for reflection might be seen as overly constraining and to imply that the steps should be followed in a particular way when experience is rarely so easily differentiated into neat, preordained categories. The model might itself impose a structure on experience that is not there making a Procrustean bed for practitioners that limits their learning and forces them into narrow ways of thinking that inhibit cognitive flexibility and fluid intelligence.

Part 4: The role of reflection in CBT

Photo by Krisztian Matyas on Unsplash