Introduction

Introduction

Sex: simple enough to have been a mainstay of animal reproduction and evolution for millennia, complex enough that there is still no fully agreed understanding of the female orgasm (Pfaus et al., 2016); liberating enough to be perhaps the most democratic form of free fun when entered into freely and without coercion, restrictive enough that people’s bodies and the rights to use them how they wish have been a battleground over which generations have fought; satisfying enough to reach the heights of ecstasy and bliss, painful enough to have been responsible for untold individual human misery in the shape of emotional anguish, sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies; inspiring enough to have been at the root of some of the most elevating human art, tawdry enough to have been responsible for the exploitation and cruel use of countless people through the ages. However we see it, whatever it means to us, it seems important that we understand and engage with what it is to be sexual and intimate human beings. The purpose of this article is not to engage in a sociopolitical critique of the role of sex in human society but simply to set out some of my ideas about the form and function of human sexual functioning as we might experience it as individuals. The following article sets out a biopsychosocial model that combines biological (physiological), psychological and social factors across various phases of experience. These phases suggest that there are distinctive features to various parts of a sexual experience, although the phases in fact build on each other, rather than each phase superseding the previous one.

This model is intended to be heuristic and descriptive – it is not based on any new research, just on what is, I hope, a careful reading of existing literature. It is probably most applicable to partnered sex but could also be extended to sex in other contexts, such as solo sex (i.e. masturbation). I have combined a description of the model with questions that readers might like to ask themselves to get a better understanding of themselves as a sexual person, or that might help inform psychological therapy for psychosexual problems. These questions focus on our individual experience of sex, including:

- What attracts us to a sexual experience, and what could put us off? and,

- What makes for a personally satisfying sexual experience?

Background

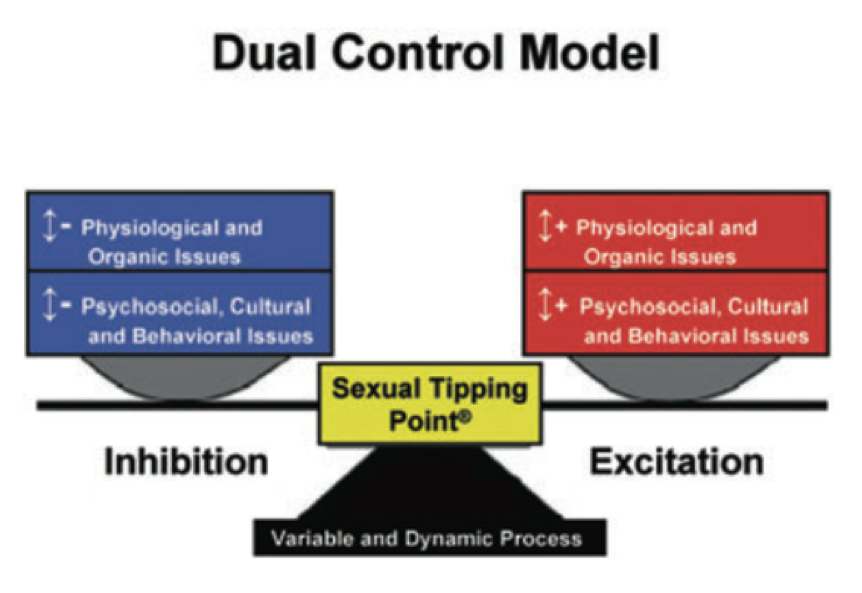

The anticipate-engage-appreciate (AEA) model is a synthesis and theoretical extension of existing models of sexual function as they have developed since the 1960s. The modern era of scientific thinking about sexual functioning begins with Masters and Johnson’s (1966) sexual response model, with its focus on the physiological phases of excitement, plateau, orgasm and resolution. Later, Helen Singer Kaplan (1974) simplified the model and introduced a psychological element in the form of desire as a precondition for excitement (physiological arousal) and orgasm. David Reed’s Erotic Stimulus Pathway Theory (Keesling, 2004) focused on a mixture of emotional and cognitive factors across four phases: seduction (the way that desire is formed within and between people), sensations (leading to physiological arousal), surrender (in order to experience orgasm) and reflection (on the meaning of the experience). That was then adapted into a circular model specific to women’s sexual response by Whipple and Brash-McGreer (1997). Their model demonstrated how pleasure and satisfaction from one sexual experience (or the lack of it) shaped women’s expectations for future sexual experiences and thus affected subsequent levels of sexual desire. Rosemary Basson (2001) then developed a more detailed circular model of female sexual functioning that aimed to show how physiological, psychological, relationship and cultural factors interact in complex ways. It described how a state of sexual neutrality (with regard to desire), accompanied by a willingness to be sexually aroused, were preconditions for sexual responsiveness, especially in women who experienced low desire. Bancroft’s (2006) psychosomatic model of sex and the dual control model (Janssen & Bancroft, 2006), proposed that sexual arousal depends on two factors: an excitation process and a separate inhibition process. These processes help us to weigh up the costs and benefits of becoming sexually aroused or engaging in sex. If the incentive to be sexual outweighs the potential costs then we reach a “tipping point” where excitation predominates; if the costs are stronger, then inhibition holds us back. I have added an Appendix after the main article with more details about some of these models.

All of these models have their insights, but I have found that in practice each does a good job of explaining some parts of the process of human sexual functioning. I have therefore tried to construct a synthesis in what I hope is a user-friendly way to understand our personal sexual functioning. The model is organised in four phases: 1) a preliminary formative phase where a person’s physical self, their psychological makeup, their personal history, and their social circumstances all interact to influence our overall attitude and disposition towards sex. In other words, the extent to which in general we like or want sex. 2) an anticipatory, appetitive phase where the meaning and context of sexual opportunities lead to greater or lesser receptiveness and responsiveness at the prospect of sexual activity. 3) a phase of sexual engagement, enactment or consummatory behaviour in which a person engages in sexual activity either alone or with another. And, 4) a stage of evaluation and appreciation where sexual activity is resolved. Our expectations about future sexual experiences are influenced through a process of reflection and learning based on how satisfying we found the experience. These reflections might be specific to a certain person, place or time, or, over time, influence more generally our attitudes to sex, to our sense of ourselves as a sexual person, and to the world as a safe and fulfilling place in which to be sexual. It is hoped that this model will therefore help to contextualise what Dillon et al. (2011) describe as the multiple dimensions of human sexuality including sexual needs and wants, sexual values, modes of sexual expression, preferred characteristics of sexual partners, preferred sexual activities and behaviour, and sexual (or group membership) identity. The model is shown in detail in Figure 1.

Influence (formative) phase factors

There are many factors that might influence a person’s overall attitude towards sex and its place in their social, romantic, and erotic life. An Ecological model describes four levels of influence: 1) factors most closely related to the person (e.g., personal attitudes and personality traits etc.); 2) factors associated with interpersonal variables, which play out in interaction with those closest to the individual (e.g., the way our own and our partner’s preferences interact); 3) factors related to more distant social variables that indirectly influence the person (e.g., our social or family support networks); 4) factors that make up the ideological-cultural world associated with social and cultural principles (e.g. the norms, laws, and practices relating to institutions such as marriage). Our adult sexual selves are formed from interactions between these levels across the developmental period from childhood, through puberty and adolescence, to adulthood. Our biologically determined, physiologically based, personal characteristics interact with environmental circumstances related to family and culture to shape our physiological, psychological, and behavioural responses to events and our self-concept and identity, an important aspect of which is our sexual self.

As a result of those four levels of formative factors, we might be said to develop an overall, general dispositions towards both our sociosexual attractions, (our social, romantic and sexual partner choices), and to sexual experience (where, when, what, how often etc.). Those dispositions are relatively enduring but can be altered by experience, changes in circumstances, and physiological processes such as ageing. These dispositions might usefully be termed trait sexual receptiveness and trait sexual responsiveness. Trait receptiveness is our level of openness to sexual experience, while trait responsiveness is our physical capacity to respond sexually and the way we behave sexually. In terms of the dual control model, trait receptiveness could be conceptualised as how sensitive we are to inhibition, in other words, how attractive or unattractive the idea of sex seems or how easily put off sex we are. Trait responsiveness could be thought of as our overall capacity and willingness to become sexually excited, that is, how well our bodies respond and how wiling we are to seek or take opportunities to be sexual. These traits are embedded in sexual schemas, which are enduring mental structures about the self as a sexual person that shape the way sexual information is understood, processed and responded to (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994, Andersen, et al., 1999).

Sexual schemas can have positive or negative attributes. For example, when Cyranowski and Andersen (1998) asked undergraduate American women how they thought of themselves as a “sexual woman” they identified two positive sexual schemas and one negative one: the positive schemas were romantic/passionate and open/direct, while the negative one was embarrassment and conservatism. Our sexual schemas reflect not just how we think of ourselves as a sexual person, but how much a person likes or wants sex and under what circumstances. As Meana (2010) points out, liking and wanting are not the same thing. We might both like sex and want sex, or not like it and not want it, or like it in general but not want it at this time or with this person, or not particularly like it but want it for other reasons, for example for relationship reassurance. Even defining what we mean by sexual can be difficult as individuals will differ in what they consider is or isn’t sexual behaviour: for example, one person’s “harmless flirting” is another person’s intimate betrayal. If we don’t experience desire, and that feels like a problem for us, we might even want to want sex (i.e. desire for desire), perhaps because we know that we have liked it, or believe we could like it, or appreciate what it has done for us and our relationships in the past, or fear the harm its absence might do to us or our relationships. Clinical experience suggests that desire for desire can even be based on the mistaken belief that a lack of sex is harmful to our physical health.

Personal factors

We are physical creatures, and it has often been claimed that we have a baseline level of sexual interest that can be seen as similar to physiological drives such as hunger and thirst and with similar motivational drives to feeding behaviour. The level of sexual motivation in animals and humans can be inferred from observing how sexually excited they become and how low or high their thresholds are for arousal, sexual activity and orgasm. In terms of humans, the incentive value of sex (how important it is to us) can be inferred from how much attention we give to sex, how hard we’re willing to work to obtain sex, and how likely we are to engage in sex when it is available (Pfaus, 1999).

The concept of a sexual drive is linked to the idea of “spontaneous” desire, which is a controversial topic as it is not entirely clear what processes cause this desire to emerge given that desire, unlike say hunger, is not vital to preserving our immediate health and wellbeing. Spontaneous desire is sometimes contrasted with the idea of responsive desire, which is feelings of desire that occur after sexual activity has started. Responsive desire is sometimes known as arousability, which is the capacity to become aroused in response to sexual activity, rather than becoming aroused before sexual activity starts. There seems to be some evidence that men are more likely to experience spontaneous desire and women responsive desire (Basson, 2001), although there may be greater differences between individual men and individual women than between men and women overall.

It might be that ideas about desire come down to the way that it is thought of differently for men and women. For example, desire in men is often linked to the idea of sexual activity as a goal, whereas in women desire, or feeling desired, may be an end in itself. It can also be easy to overlook the fact that men’s desire is also contextual and responsive to sexual cues, even if those triggers are out of awareness (Meana, 2010). Nonetheless, the concept of desire, the way it is experienced, and how it fluctuates or intensifies across sexual activity, is central in this model because it is seen as the motive force behind developing and maintaining an interest in sexual activity.

Our developing sense of self-worth or our self-esteem more generally also influence our sense of ourselves as a sexual person, as does our body image and our satisfaction (or lack of satisfaction) with it. These are clearly influenced by interpersonal, peer, and social factors. Our personality also shapes our tendency to approach or avoid sexual stimuli or to seek diverse sexual stimuli. For example, the strength of our tendency towards sensation-seeking in all areas of life will influence how we think, feel and act sexually (Zuckerman, 1983).

We are also thought to develop a restricted or unrestricted sociosexual orientation, a term originally devised by Alfred Kinsey. Sociosexual orientation refers to the differences people have in their willingness to engage in sexual activity outside of a committed relationship. People with an unrestricted sociosexual orientation tend to be more open to casual sexual experiences, whereas those with a restricted orientation tend to prefer greater love, commitment and emotional closeness before being prepared to engage in sex with a partner. Sociosexual orientation can be evaluated in terms of three factors: the extent to which someone has casual or changing sexual partners; their attitude towards uncommitted sex; and feelings of desire for people with whom one has no romantic relationship (Penke, 2011).

Another relevant developmental factor is our attachment style, which refers to our capacity to manage emotions in relationships and our preferences for emotional closeness or distance. Attachment is usually described in terms of three styles: secure, avoidant or anxious/ambivalent. Each style influences the function of sex for us. If we have an avoidant style, we may find emotionally intimate sex very uncomfortable; if we have an anxious/ambivalent style, we may use sex as reassurance that the other person won’t abandon or reject us. If we have a secure attachment style, we are more likely to be able to balance emotional intimacy with sexual passion, neither objectifying the other person, nor thinking of sex primarily as a tool to soothe relationship anxiety (Davis et al., 2004).

Interpersonal factors

Our previous sexual experiences, both happy and unhappy can be powerful and memorable. Most children have some experience of pre-puberty sexual play or body exploration, often as result of their curiosity about this mysterious adult preoccupation that they see or hear about (Friedrich et al., 1991). Children’s sexual play has a very different purpose from adult sexuality and should not be confused with it. How those experiences made us feel and how they were dealt with if and when adults became aware of them, can lead to lasting strong feelings. These earlier experiences may also shape by association what we find erotic. It has been suggested that men’s sexual “templates” are formed earlier and are more firmly fixed than women’s, such that women are often described as being more likely to have a fluid or “plastic” (malleable) sexuality, although there are differing perspectives on this (see Baumeister, (2000, 2004) and Diamond (2016), for differing viewpoints). However, these are generalisations and it’s important to remember that individuals remain very diverse, whatever their gender identity.

Social and cultural factors

Factors that influence our trait receptiveness and responsiveness include social influences, such as the messages we received about sex from parents, peers, authority figures, and the media, both traditional and social. These messages tell us what’s considered right and wrong or good and bad; they communicate approval or disapproval, and include messages about gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual practices and gender roles. We can’t help but learn a set of values, beliefs, and expectations about sex in the context of our particular society, race and class, even if we go on to reject them. We also acquire our theoretical knowledge of sex through diverse and sometimes not entirely reliable sources. Clinical experience suggests that some young people, especially young men, are learning sexual scripts from the stereotyped sequences of sexual activities portrayed in online pornography, with sometimes embarrassing or distressing consequences when they attempt to enact them in partnered sex.

In order to understand some of these influences on your development as a sexual person, you might like to consider what effect the following areas of your life have had on how you think and feel about sex, relationships and intimacy:

- The way you learned about sex and how that made you feel.

- Your upbringing and its effect on your sexual attitudes, beliefs, and values (e.g. the role and value of sex in or out of a committed relationship, or the importance or centrality of intercourse/penetration to sexual satisfaction).

- Your personality, for example in terms of enjoying and seeking novelty and new experiences versus contentment with the familiar or a more cautious approach to life.

- Your worst, or least satisfactory, sexual experiences and your best, or most satisfactory, sexual experiences.

- Your view of yourself as a person and your overall self-esteem and self-acceptance (e.g. seeing yourself as fundamentally lovable, likeable, or successful).

- Your perception of your body, or of your overall physical attractiveness.

- Your perception of how knowledgeable you are about sex.

- Your areas of uncertainty, doubt or confusion about sex and what might be seen as “normal” or “abnormal”.

- Your perception of your competence and skilfulness as a sexual partner, including your ability to offer a partner a positive sexual experience.

- Your attitudes towards emotional closeness and intimacy and your beliefs and values about relationships.

- The attitudes of your family, friends and peers, and their behaviour.

- Your gender identity and sexual orientation.

- The attitude of the communities with which you identify, or that you live in.

- The attitude of society in general.

Anticipation (appetitive) phase

Whatever our general dispositions to seek out or avoid sexual activity, decisions are made in the moment. People choose to engage or not in sexual activity based on a number of potentially conflicting factors including 1) current circumstances, such as the characteristics of any perceived opportunities for sex, 2) the self and how we currently feel, such as our mood or state of physical health, 3) interpersonal and social factors, such as experiencing mutual attraction, our verbal and nonverbal communication, and the norms, rules or laws regarding the appropriateness of sex, and 4) our capacity to consent, that is to make an informed judgement, free from coercion, as to what is in our best interests.

Our immediate incentive and willingness to engage in sexual activity depends on both our state receptiveness that is, how open we are to internal or external sexual signals in the moment, and our state responsiveness, which is how we respond physically and behaviourally. Both depend on the perceived function of sexual activity, which may be focused internally (e.g. on personal pleasure, tension release, a boost to self-esteem), externally (e.g. on another’s pleasure), interpersonally (e.g. to enhance a relationship), or socially (e.g. to fulfil an obligation to society). Becoming pregnant is also a potential function of some types of sexual activity, although whether that is a personal, external, interpersonal, or social function depends on the individual and their circumstances. Of course, at different times and on different occasions the function of sex can change depending on what it is that we want to get out of it. This can cause difficulties for couples who are struggling to conceive when the function of sex and the behaviours that surround it can make the pleasures of sex seem secondary to conception, placing a lot of pressure on people to be receptive and responsive according to a timetable or a temperature reading.

Internal factors relating to the self that influence our incentive for sex might include our physical responsiveness due to our age and stage of life, our body image and sexual self-esteem, our physical and mental health, and our mood (e.g. excitement, boredom, anger etc.). External factors, in other words our social circumstances, might include the availability of an attractive and willing sexual partner, the nature of the setting and how conducive we find it, and our level of privacy. Interpersonal factors include our relationship status and how satisfied we are with it, our capacity and willingness to communicate to a partner what we want and don’t want, and our perception of our role in a relationship.

Deciding whether to engage in a sexual activity should always be a free choice made with full informed consent, free from coercion. Our capacity to give consent depends on a number of factors, including: 1) our understanding of what is involved, which may be influenced by our age and emotional maturity, 2) our current state of mind and whether we are sufficiently sober to know our own mind and make an informed judgement, 3) our ability to communicate our wishes, and 4) the extent to which we feel under pressure to conform to some other person’s wishes and are able (physically and psychologically) to resist unwanted and unwelcome sexual advances.

The more reflective, confident, capable, safe, and supported we feel in our decision-making. the more this process will involve consciously weighing up the pros and cons of sexual activity without being unduly influenced by other factors that might affect our judgement. If the cons outweigh the pros, then we are likely to be unresponsive to the idea of a sexual experience and decline to engage in sex or refuse it. If the pros outweigh the cons, and sex is freely chosen for personal as well as interpersonal goals, then we cross a sexual tipping point where sexual excitement (or the possibility of it) is greater than any potentially inhibiting effects. Inhibiting factors are anything that might dampen the possibility of sexual activity. These could be physical (e.g. low desire, pain), cognitive (e.g. expectations of performance failure or judgement), emotional (e.g. feelings of shame, guilt, anxiety or other negative emotions), social (e.g. potentially falling foul of laws that restrict or prohibit certain types of sex or sex between specific people), or cultural (e.g. sex between unmarried partners in certain religious traditions).

The relationship between sexual inhibition and excitement is likely to be determined by a complex system of interacting factors (Bancroft, 2009). While being sensitive to factors that inhibit us leads to a low probability of being responsive, high levels of excitement in the absence of inhibition should lead us to seek out or engage with sexual opportunities. Where there is a mixture of factors that inhibit us but also excitement at the possibility of sex (for example, in the presence of a sexually attractive person, while a bit drunk, but being in an exclusive relationship) there is likely to be a degree of conflict and confusion that might be felt as ambivalence. Eventually either excitement or inhibition wins out and resolves the situation, and the possibility of sexual activity either ceases or is consummated. If both inhibition and excitation are low then the person may be in that state of sexual neutrality that Basson (2001) described as a potential precursor for women to become responsively sexually aroused, if they are willing.

Sexual excitement and inhibition should not be considered either good or bad in themselves; they depend on context. Sometimes inhibiting a possible sexual response is exactly the right thing, for example to avoid the possibility of unsatisfying, counter-productive or dangerous sexual activities. This is especially true if, for example we can be influenced by, or tend to be overly compliant with, another person’s sexual preferences. Or, we might be vulnerable to act on urges towards a sexual activity that carry potentially negative consequences, such as an unwanted pregnancy or a sexually transmitted infection. Sexual desire and arousal can have a powerful influence on our judgement, so attending to information that supports sensible inhibition is helpful and adaptive in circumstances that are potentially threatening or unsafe.

In order to understand your own sexual anticipations better, try answering the following questions about the factors that affect the likelihood that you would want to engage in a sexual activity at a given time:

Internal factors (or, being in the right frame of body and mind):

-

-

- How do you feel about your body right now – it’s good and bad points – and what effect does that have on your attitude to sex?

- What kind of mood makes a difference to whether you think you would enjoy sex?

- What emotions do you feel at the prospect of sex?

- How does your current age, physical health and mental wellbeing affect your ability to become aroused and experience desire?

- How does any prescribed medication you take affect your ability to become aroused?

- How do any recreational substances you use (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, street drugs) affect your ability to feel desire and become aroused?

- How strong is your sex drive or appetite for sex right now?

- To what extent do you anticipate problems with your sexual performance (e.g. problems with arousal or orgasm or pain)?

- To what extent do you anticipate potential negative consequences of a sexual experience or sexual approach (e.g. pregnancy, infection, negative judgment, rejection, mockery and humiliation)?

- To what extent are you conflicted about the possibility of a sexual experience (e.g. feeling moral ambivalence)?

-

External factors (or, being in the right situation)

Person

-

-

- If you’re considering partnered sex, what aspects of the other person contribute to your desire (or the possibility of it) or attraction to them (e.g. aspects of personal hygiene, their state of mind or recent behaviour, the way they dress or their physical attractiveness)?

-

Place

-

-

- What situations do you associate positively with sex?

- What situations do you associate negatively with sex?

- What kind of settings (e.g. at home in the bedroom, on holiday in a hotel room, in the outdoors or in nature etc.) help you to feel open to the idea of sex?

-

Time

-

-

- Is there a particular time of day, or day of the week, or time of the month, that suits you, or that you prefer, for sex?

-

Activities

-

-

- Are there any specific activities that heighten your sexual interest (e.g. exercise, dancing, watching or reading erotic material, a romantic meal)?

-

Interpersonal/lifestyle factors

Circumstances

-

-

- What access do you have to a person or people that you find sexually attractive or desirable, i.e. how available is a sexual partner (if relevant to you)?

- What access do you have to erotic material that you find arousing, or sexual aids, if relevant (e.g. erotica, pornography, sex toys etc.)?

- What else might be going on in your life that could have an effect on your attitude to sex (e.g. stressful life circumstances)?

-

Relationship

-

-

- If you have a partner, what expectations do they have of you as a sexual partner and how does that affect you?

- How well do you and your partner communicate about whether or not you might want to be sexual with each other, or your preferences and dislikes?

- If you have a partner, what do you imagine or hope that they think of you as a lover – what are your best points and what are potential areas where your love-making skills might be enhanced?

-

Consent

-

-

- How do you communicate consent, that is, let a partner or potential sexual partner know that you are either willing or unwilling to engage in a sexual experience with them?

- How would you let a partner, or potential sexual partner, know that you have changed your mind about your willingness to have sex, in other words that you have withdrawn your consent?

- What do you do that increases or decreases your ability to make an informed judgment whether to have sex (e.g. monitoring your level of intoxication)?

- Under what circumstances might you act with sexual intent or seek a sexual experience for short-term benefits despite feeling conflicted about it or believing that it is not in your long-term interests?

- What kinds of circumstances help you feel safe and which might seem risky (e.g. going back to a stranger’s place on a first date).

-

Social factors

-

-

- What types of sexual activities or sexual partner preferences are regarded as appropriate or inappropriate in your society or culture that might have an effect on you?

- How are those sexual activities policed or enforced in both a statutory (legal) framework and in terms of the approval or disapproval of culturally significant authorities (e.g. religious figures) and what effect might that have on you?

-

Functional factors (acting for the right reasons)

-

-

- What could be the main benefits of initiating or agreeing to sex for you, for example sexual pleasure, tension release, relationship enhancement (romance and intimacy), the possibility of getting pregnant, a boost to self-esteem etc.?

- What could be the main drawbacks of initiating or agreeing to sex right now e.g. an anticipated lack of pleasure, increased tension, relationship conflict (lack of romance or intimacy), the possibility of getting pregnant or a sexually transmitted infection, damage to self-esteem etc.?

-

Engagement (consummatory) phase

As well as being responsive to opportunities, people are also active creators of their circumstances, so may seek out sexual experience or prepare for the possibility, when either sexual desire arises, or they perceive the potential for obtaining the sexual interest of another, desirable person. In contrast, if sexual activity is not seen as likely to be rewarding or has little interest to the person, they are likely to be unreceptive to the idea of sex and unresponsive to the possibility of it, avoiding, ignoring or discouraging the possibility. However, in the right setting, with the right person, at the right time, in the right frame of mind, with the capacity and willingness to communicate consent, and when sufficiently motivated by desire (or the prospect of desire) to engage in sexual activity, and to respond with emotional and physiological arousal, we transition to a phase of active engagement with a sexual experience.

Although these phases are distinguished for the sake of highlighting components of the model, in reality they may flow into one another and be less clearly distinguished as receptiveness flows into responsiveness, which in turn flows into sexual activity. An inability or reluctance to distinguish between an anticipatory phase and a phase of active sexual behaviour can make consent hard to communicate, especially if verbal and nonverbal communication is poor, inhibited, neither sought nor offered, or is inadvertently or wilfully misunderstood or ignored. This is particularly difficult as behaviours may be interpreted as more or less sexual and/or have relational significance. Courtship behaviours, such as flirting for example, may be seen as signalling romantic interest with a view to exploring the prospect of a more emotionally committed relationship, a signal of sexual interest that is a precursor to (hoped for) sexual activity, or be seen as a stimulating and rewarding end in themselves. Interactions between people in a sexual context therefore depend on the interpretation and meaning of behaviour to each person as well as their ability to communicate openly and effectively what is intended and understood by their actions. Communicating effectively can be highly challenging when sex is experienced as a potentially vulnerable activity to seek or to engage in, for example carrying the risk of rejection. As a result, the balance of sexual inhibition and excitement processes are often in a dynamic flux in all phases of the sexual experience, rather than reaching an irreversible tipping point.

In a consummatory or engagement phase of sexual activity a number of cognitive, behavioural, physiological and emotional factors come into play that will either maintain and deepen desire and depth of involvement or bring the experience to an end. Sexual desire, as we have seen, is the term that’s most often used to describe the motivation for sexual activity. Motivation is sometimes described as the desire to act in the service of a goal, which is why it can help us to understand the function of sex at any one time, in other words, what we hope to get out of the experience as well as what we think will help us to achieve that goal. That can include specific sexual activities or settings that enhance desire, arousal and overall pleasure and fulfilment. As we have seen, our goals can range from seeking to get pregnant to a self-transcendent experience of bliss or ecstasy, to a brief but intense sexual thrill. If you’re having sex with a partner, then it helps if you are both explicitly seeking the same goals from your sexual experience. Even if you’re having sex on your own, it can help to keep your goals realistic and achievable so that you don’t set yourself up for disappointment. The issue of having realistic, shared goals for sex is addressed in Metz and McCarthy’s (2007) Good Enough Sex model, which helps people to anticipate and come to terms with the fact that not all sex is Earth-shattering and sometimes it can be pretty unremarkable or downright disappointing.

Eroticism

Cognitively, a person needs to appraise or judge the situation as one that, at a minimum, is acceptable to them, and preferably is one that is consistent both with their preferred erotic perceptions, expectations, and fantasies and with maintaining a positive evaluation of self, partner and the experience itself. Erotic thoughts (cognitions) are the psychological component of desire. People differ in what they find erotic, which is influenced by our history of associations between sexual arousal and the objects or setting in which that arousal takes place. Our erotic imagination includes our fantasies and desire for specific forms of sexual stimulation.

Attention

Focused attention is also at the heart of sexual responding because it is about what we are paying attention to. Three things that can enhance desire and arousal are 1) the signs of our partner’s arousal (for example the signs of pleasure that they might be making), 2) our entrancement with the physical sensations we are experiencing to the exclusion of any possible distractions, or 3) the fantasy content of our minds or that are being acted out by another, either in person, in imagination or on screen (Mosher, 1980). If we start to focus instead on negative thoughts about how we look or sound (what Masters and Johnson called spectatoring) then we can quickly experience a loss of arousal as we become increasingly self-conscious. In men this could manifest as erectile dysfunction.

Arousal

Physical arousal describes the body’s physiological responses in anticipation of and during sexual activity and comprises the engorgement of sexual tissue leading to erection in men, and vaginal lubrication and widespread engorgement of sexual tissue in women. These are key components of sexual pleasure. Problems with arousal are an area that causes many psychosexual problems, such as a lack of lubrication in women, or erectile dysfunction in men. Arousal processes are affected by ageing; in older men erections become less reliable and long-lasting and in menopausal women there is a reduction in vaginal lubrication and thinning of the vaginal wall. These latter problems often respond positively to medication. Physical arousal may wax and wane throughout a sexual experience, so it is important not to get too hung up on or catastrophise about, for example, the temporary loss of a firm erection. Couples, across the lifespan, need to find flexible behavioural responses that respect the fact that the human body can be fallible (Metz & Mccarthy, 2007). Even a young, fit and healthy body is likely to fall short in the face of unreasonable physical and psychological demands.

Sensation

The body is the source of sensory stimulation through the five senses, and the extent to which these are perceived as pleasurable and erotic helps shape both desire and arousal. The body is covered in sense receptors that respond to tactile stimulation (e.g. touching, licking, stroking), especially in the erotic or erogenous zones that include the genitals, although pretty much any part of the body can become erogenous in the right setting. Sensations that are perceived as unpleasant, whether that is smell, touch, sight, sound, or taste, may be off-putting and lead to a loss of desire and depth of involvement. Sensory stimulation through non-sexual touch is key to sensate focus, which is Masters and Johnson’s main behavioural therapy for psychosexual problems. Couples work through a series of exercises where they are instructed to take turns to give and receive pleasurable touch whilst focusing only on the sensations and any accompanying feelings of physical entrancement, curiosity or pleasure that result. In this way, couples are taught to pay focused attention to physical stimulation, which reduces the chances for anxiety to cause distraction or loss of arousal.

Feelings

Feelings refers to our sense of liking or disliking something. This is a very basic level of emotional response but an extremely important one. Sexual arousal and behaviour even in animals is a complicated mixture of nature and nurture, of instinct and learning, that is of unconditioned and conditioned responses (Pfaus et al., 2001). An unconditioned response is an instinctive reaction to certain stimuli, such as the sight or sound of sexual activity, or to the presence of specific scents. It has been suggested that human sexual behaviour is influenced by pheromones, although to what extent is not entirely clear (Grammer et al, 2005).There is also evidence that decisions we make to influence liking and disliking, such as the choice of fragrance, is linked to gender differences and sexual orientation, with heterosexual men and women wearing scents that are intended to be attractive to the opposite sex, gay men having a strong preference for “musky-spicy scents for themselves and their partners, and lesbians showing varied preferences (Muscarella et al., 2011)

Tis unconditioned element of liking and disliking occurs completely independent of any thought processes. It is similar to the way that we salivate at the smell of food cooking. Similarly, things that we strongly dislike can also produce an unconditioned response, for example when they produce a reaction of disgust. However, sexual responses can also be conditioned, although this tends to occur more readily in men than women (Hoffman et al., 2004). When we pair an emotionally neutral situation, person or activity with a situation that triggers an unconditioned sexual response, eventually the neutral situation, person or activity is enough to trigger the sexual response on its own. This process of learning, or training our feelings by association, is called classical conditioning – it is literally a Pavlovian response. It may be responsible for many of our sexual preferences, and can be completely benign, for example when we come to associate a certain person or place with sexual activity so that just being there or with that person creates a sexual response. it can also have problematic consequences, because it may contribute to the development and maintenance of some potentially destructive or illegal sexual behaviours, such as voyeurism or paedophilia (Kaplan & Krueger, 2012, Pfaus et al., 2020). Pairing sexual arousal with an aversive stimulus, such as an electric shock, has a sad and abusive history in behaviour therapy. It was used, cruelly and without justification, as a form of so-called “conversion therapy”, mainly to try to rid gay men of their sexual attraction to other men. There is a moving and sad account of the experiences of such patients in the UK from the 1950s in a paper by Brown et al. (2004).

Another form of learning that relates to liking and disliking is reinforcement. if an experience evokes pleasure and liking, we are more likely to repeat the behaviour that led to the experience. if we dislike it, or we find it unpleasant, we are more likely to try to avoid it in future. To the extent that we manage to avoid something that we think will be unpleasant, we are rewarded for our avoidance by the feeling of relief. This means we are more likely to avoid it again in the future. This pattern can lead couples into difficulty when avoiding an activity becomes unintentionally rewarding, leading to a cycle of diminishing interest in and engagement with opportunities for sex. A combination of classical conditioning and reinforcement can contribute to sexual aversion. For example, if sex becomes associated with pain, for example in the development of extremely painful conditions such as urinary tract infections, the association of sex and pain can cause people to avoid intimacy. In so far as avoiding sex brings relief from anxiety, avoidance will be reinforced. This process can lead some couples into frequent conflict if the avoidance of sex feels like a deprivation or loss of valued intimacy. Sometimes, the partner who was seeking sex will in turn avoid sex, feeling relief at avoiding an argument. Avoidance can also generalise so that couples avoid not just sex but any form of touch that might signal the possibility of sex – in this way the couple have mutually reinforced each other for avoiding not just sex but any physical intimacy, which can lead to a loss of closeness.

A third learning process that influences liking and disliking is habituation. Although habituation processes are still not well understood, they play a big part still in treatments to overcome phobias. With repeated exposure to the phobic trigger, whether dogs or heights, or needles, the fear response diminishes. However, habituation, also reduces the intensity of pleasurable experiences with repeated exposure. If sex becomes too predictable and repetitive we can habituate to it, no longer liking so much what we previously enjoyed and even finding it aversive. This is not necessarily a recipe to pursue ever-more diverse forms of sexual stimulation to overcome boredom – it is possible that it is not the repetition that is important but the way that we pay attention to sensations. If we are able to remain mindful of our own and our partner’s pleasure, then we can learn to appreciate and savour the uniqueness of this experience no matter how often we have experienced something similar. There is also a darker side to habituation, which is when we learn to get used to something that we actually don’t like or that demeans us. Habituation is fine for learning to love olives, even if our initial reaction was distaste, but it is more insidious if it is in the service of fulfilling one person’s sexual desires at the expense of their partner’s preferences.

Emotions

Emotions are a more developed form of liking and disliking. They too are generally positive or negative, but just as smell is a more complex phenomenon than taste (we can distinguish thousands of smells but only five tastes), so emotions are enormously complex and sensitive. The delightful subtleties of our emotional world are potentially built from a palette of six basic emotions, although the reality is probably a lot more complicated (Ekman,1999). How we think is often said to make the difference. A positive emotional state of excitement, joy, intense eroticism, or delighted surprise in one’s own or one’s partner’s behaviour, is dependent on seeing the situation as pleasurable and rewarding. Where the situation evokes unwelcome feelings of anxiety, disgust, shame, envy, jealousy or guilt, it is likely to interrupt both the process and the level of desire experienced. Anxiety is particularly destructive. it can lead to self-consciousness in sexual situations and a focus on performance in pursuit of a sexual ideal, rather than focusing on one’s own and one’s partner’s pleasure. In men, anxiety can paradoxically cause either erectile dysfunction or rapid ejaculation. Typically, positive emotions enhance our experience of sexual pleasure whereas negative emotions can diminish it. It is perhaps worth pointing out that these roles can be reversed – sometimes positive emotions can be aversive if we have learned to associate them with unpleasant events and negative emotions can be attractive, if we have linked them to sexually arousing situations. This can cause some people, for example, to seek experiences of shame and humiliation for sexual gratification because they have become associated with sexual pleasure.

Action

Sexually stimulating acts or behaviour are also key to sexual pleasure and stimulation. Most sexual acts involve touch in some form (except perhaps when acting out a fantasy to an observer) and so are intimately connected with sensory stimulation. The kind of touch or physical interaction we enjoy, and the parts of the body that we enjoy having stimulated and in what order or sequence, is highly personal, whether that’s in how or whether we kiss, or experience penetration, or stimulate and arouse each other with mouth or any other part of the body. Behaviourally, a person needs to engage sexually in a way that feels right for them, whether that involves a focus on involvement with their partner, sexual trance, or role play (Mosher, 1980). They need to appraise both their own and their partner’s behaviour as appropriate, skilful and attuned to each other’s needs. The focus of behaviour will ideally be on one’s own and one’s partner’s pleasure, whether that is in the giving of pleasure to another, the allowing of another to take pleasure in oneself, the taking of pleasure in one’s partner, or receiving sexual pleasure that is offered, as Betty Martin describes in her Wheel of Consent model (Martin, n.d.).

Interactions: communication

Reciprocal verbal and nonverbal communication are important processes in maintaining consent and getting feedback on what is wanted or desired, and what is not wanted or feels unwelcome or inappropriate. In contrast, when behaviour is uninvolved, passive and uninterested, routine or disengaged, or when it is overly inhibited, unskilful, or insensitive, it is likely to have a negative impact on levels of desire and depth of involvement. Similarly, if the function of sexual behaviour is mismatched with one’s partner, for example when one person is seeking only their own physical satisfaction while the other is seeking emotional closeness, then this may cause a disconnection from the experience of pleasure. If sexual behaviour is functioning to manage a craving, as in the case of a sexual compulsion, then again, this is likely to detract from the shared interpersonal experience.

Desire

While desire is probably central to all of the other components in this phase, each may well be necessary for a pleasurable and sexually satisfying experience. There is a complex interplay between our motivation (desire), our thoughts, our feelings, the focus of our attention and how this sexual act, at this time, in this place, makes us feel in terms of our physical arousal, our erotic imagination, our emotions and our senses. It’s worth remembering that motivation to engage in specific sexual acts can change as your level of arousal and depth of involvement increases. This is because some disgust or aversion responses get inhibited by sexual arousal, so we might find ourselves feeling OK with something at the time that later we come to look on with rather different feelings. Sex could therefore be thought of as a kind of dance where consent is repeatedly re-negotiated through asking and answering either implicitly (non-verbally) or explicitly (verbally) whether this feels OK or whether more or less of that at this time would be good.

In order to explore your experience of each of these components, you might like to consider these questions:

Motivation/Desire

-

-

- What are your main reasons for engaging (or not) in sex right now?

- What do you hope to get out of it?

- What might prevent you from meeting your goals or inhibit you in this situation?

- What other, perhaps less obvious reasons, might be motivating you to agree to something you’re not sure of, or decline something that you might enjoy?

- What helps you to deepen your feelings of desire?

- What is it about sex that brings you the most pleasure?

-

Physical arousal

-

-

- To what extent are you happy with your ability to become physically ready for a sexual experience (e.g. erection, lubrication)?

- To what extent are you able to maintain your physical arousal throughout the experience for as long as you would like?

- To what extent does pain or other physical responses (e.g. vaginismus) interfere with your ability to become aroused, maintain your arousal for as long as you would like, or engage in your preferred sexual activities?

- If you have tried to overcome problems with physical arousal, what have you tried (e.g. Viagra) and how successful do you think it’s been?

-

Erotic desire

-

-

- To what extent do you perceive that your sexual experiences to be agreeable, pleasant and in accord with your values?

- How well do your sexual experiences match your preferences for sexual activities?

- How well do your sexual experiences match your sexual fantasies or erotic imagination?

-

Attention

-

-

- To what extent are you able to become absorbed and entranced in the experience?

- To what extent are you able to maintain focused attention on erotic and pleasurable aspects of the experience?

- To what extent do you become distracted from erotic and pleasurable aspects of the experience?

- To what extent do you focus on non-erotic aspects of the experience?

- To what extent do you become self-conscious during the experience, as if seeing yourself from an outsider’s perspective?

-

Feelings

-

-

- What types of activities, touch, or situations do you like?

- Which do you dislike?

-

Emotion

-

-

- To what extent do you have a positive emotional response, for example characterised by desire, excitement, intimacy or pleasure?

- To what extent do negative emotions such as embarrassment, fear, disgust, shame, guilt, anger, jealousy, envy or sadness interfere with your ability to enjoy the experience?

-

Sensory stimulation

-

-

- How do you like to be touched?

- What parts of your body don’t feel enjoyable to have stimulated or are “out of bounds” for you?

- How does your partner (if relevant) like to be touched?

- What parts of their body do they not like to have touched, or not have touched in certain ways?

-

Sexual behaviour or acts

-

-

- What sexual behaviour do you engage in that increases your own sexual pleasure, desire and level of arousal?

- What sexual behaviour do you engage in that increases your partner’s sexual pleasure, desire and level of arousal?

- What sexual behaviour would you like to engage in that you feel inhibited from engaging?

- In what respects is your sexual behaviour potentially unsafe for you and/or your partner?

- In what respects is your sexual behaviour (or your partner’s behaviour) unpleasant or disagreeable?

- In what respects is your sexual behaviour (or your partner’s behaviour) lacking in skill, finesse or sensitivity

-

Communication

-

-

- How well do you and your partner communicate during sex?

- How easy or difficult is it to read your partner’s thoughts, feelings and intentions from their behaviour?

- How well do you communicate about sex outside of “the bedroom”?

-

Appreciation (reflection) phase

If the situation continues to be seen as positive and rewarding, then sexual behaviour is likely to continue to a point where one or both partners have experienced peak pleasure, or their sexual desire is sufficiently sated. At this point sexual activity enters a reflective phase in which the activity is resolved. This may occur for example after orgasm but is not necessarily dependent on orgasm for all people in all sexual encounters. However, Metz & McCarthy (2007) report that many couples suffer sexual problems at times, and not all sexual experiences are as positive as might be hoped. Sexual activity may be experienced as disappointing, unpleasant or displeasing for one of both partners when their hopes and expectations are not met. For example, an orgasm may occur more rapidly than is desired, bringing the sexual activity to an end before sufficient or peak pleasure has been achieved, as in the case of rapid ejaculation. Or, orgasm may be sought and hoped for, but proves impossible or difficult to achieve, as in delayed ejaculation or anorgasmia. Pain or discomfort, either physical or psychological, may interfere with the ability to engage and surrender oneself to sensual, and erotic pleasure. One’s own or partner’s behaviour may fail to delight sufficiently, perhaps coming across as too inhibited and self-conscious, or wild and abandoned, for your tastes. On occasions when sex is disappointing or not pleasurable, which may be between 5% and 15% of the time for couples who do not otherwise report an enduring sexual difficulty, Metz and McCarthy recommend that couples learn and are willing to accept variability in sexual responsiveness and outcomes. It can help to make sure that you communicate about disappointments and what might help in a non-judgemental, critical or blaming fashion.

Following on from a point of sexual satiety, or peak satisfaction, many people find that the major personal and relationship benefits of sex occur during the period of “after-play” during which couples may continue to take pleasure from the sexual experience and from the closeness they feel to their partner at that point. This too is a sexual activity, although it is not focused on increasing desire and arousal but on savouring the experience together. The exact form that this will take will depend on the expectations and preferences of each partner, but it can be a powerful contributor to the overall sense of satisfaction that individuals get from the experience. Even when sex has not been as satisfactory as was hoped, or has been actively disappointing, the comfort and closeness of after-play can ameliorate disappointment, whatever the experience has been. In contrast, where after-play is experienced as inadequate, for example because it is perceived as too emotionally distant or as inconsiderate, or, perhaps, too intimate for comfort (as is sometimes the case in casual sexual encounters), then it is likely to contribute to dissatisfaction.

In so far as any given sexual experience is seen as positive and satisfying, it is a potential contributor to future receptiveness and responsiveness. To the extent that sex has been evaluated as unsatisfactory or unsatisfying, it may lead to future avoidance or a disinclination to engage with sex. Lawrance and Byers (1995) have proposed an Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction (IEMSS). This model describes a process whereby sexual satisfaction is evaluated over time based on how people perceive the costs and benefits of the sexual relationship. There are three aspects to this. If people 1) see the rewards as greater than the costs, and, 2) these rewards match how a person expects sex to be, and, 3) the rewards are seen to be shared equally between partners (i.e. one person does not benefit significantly more from sexual activity than the other), then satisfaction is typically higher, especially when the couple see the overall relationship as satisfying. In couples where sex forms a fulfilling part of the relationship it is likely that it does so through paying attention to each other’s pleasure as well as to one’s own enjoyment, without placing excessive expectations on what should or could be achieved.

Balzarini et al. (2021) explored how couples evaluate their level of sexual satisfaction and how that relates to their sexual ideals. Sexual ideals means the traits and attributes a person looks for in a sexual partner and the ideal characteristics of a sexual experience. They reported that, in general, when a person’s sexual partner or sexual experience falls short of the ideal, it has a negative effect on sexual satisfaction, perhaps not surprisingly. However, if a person thought that their partner was motivated to meet their sexual needs (that is, they were doing their best), then the impact on sexual satisfaction was less pronounced. The suggestion was that, overall, a if a couple focus on meeting each other’s needs more than on meeting their own, even when sex falls short of what would be seen as ideal, couples remain sexually satisfied. Ideally, a high level of communication about sexual wants and desires enables couples to meet both their partner’s needs and to get their own needs met.

Sexual activity, like any behaviour, always offers the opportunity for learning. Each sexual experience can be understood in the context of the person and their circumstances. If the sexual experience has been satisfying, it is likely to enhance a person’s overall self-esteem, a positive sense of themselves as a sexual person, and their relationship satisfaction. If it is unsatisfying, then it may damage self-esteem, reinforce a negative sense of oneself as a sexual person, and diminish relationship satisfaction. It may also set the stage for future expectations of sexual incompetence or dissatisfaction. However, even seemingly negative experiences provide potential opportunities for learning, in so far as people are able to make sense of their experience and adapt their behaviour and expectations as a consequence. In the context of a caring relationship with open and respectful communication, a great deal can potentially be learned about each person and their vulnerabilities from a disappointing sexual experience. This learning, and the empathic joining that goes with opening up emotionally to another person, can enhance relationship intimacy and strengthen the couple bond by reflecting compassionately and with care on disappointments or difficulties with sex.

The following questions are designed to help you understand better what makes sex rewarding or dissatisfying:

Peak pleasure

-

- What is the peak of sexual pleasure for you?

- What tells you your partner is sexually sated?

- How important is your experience of orgasm to you – how important is it to your partner that you have an orgasm?

- How important is your partner’s orgasm to them? How important is their orgasm to you?

- What does it say about you or your partner if one or both of you doesn’t have an orgasm or orgasms?

- What problems do you or your partner have in achieving as much sexual pleasure as you would like?

- What gets in the way of experiencing peak pleasure for you or your partner? What do you think might help?

After-play

-

- How do you like your sexual experiences to end?

- How important is it to you to have physical and emotional closeness with a partner after you have finished actively making love?

- What do you find disappointing, unsatisfactory or off-putting about the way that sex concludes?

Satisfaction

-

- How comfortable are you with the frequency of sex and why?

- How happy are you with the quality of the sex you have and why?

- What has to have happened during sex for you to feel genuinely satisfied with the experience?

- What is the most off-putting thing about a sexual experience for you?

- What is the best and most rewarding thing about a sexual experience for you?

- If the experience has been less than optimal for you or your partner, what helps you to feel OK about it and not put off from trying again at a later time? What helps your partner?

Conclusion

Many diverse models of sexual functioning and satisfaction have been developed from the 1960s onwards. Earlier models tended to describe sex from a physiological perspective and as a linear process. More recent models describe sex as a biopsychosocial, circular process. Men’s and women’s sexual functioning may differ in significant ways due to differences in experienced spontaneous desire, especially in the context of long-term relationships (Basson, 2001). It should be remembered however that all models are generalisations of experience and the differences between different women and differences between different men are likely to be greater than any average difference between men and women. A person’s overall level of satisfaction with their sexual functioning is influenced by formative experiences, their personal sexual history, their sense of themselves as a sexual person (including their gender identity and sexual orientation) and their current relationship and social context. The anticipate-engage-appreciate model presented here is an attempt to describe the multiple, complex, interacting pathways of sexual experience as they unfold over the course of a single sexual experience, and, through a process of learning and adaptation, across the lifespan.

Resources

If you are planning to use the model in a therapeutic setting, you might find it helpful to refer to either a blank version (Figure 2) or a version with a focal question for each component to prompt reflection (Figure 3).

You can download pdfs of them here:

- A version of the full model as shown in Figure 1

- A version of the model with focal questions for each component

- A blank version of the the model

- A copy of the focal questions in a text format

Appendix 1: contemporary models of sexual functioning

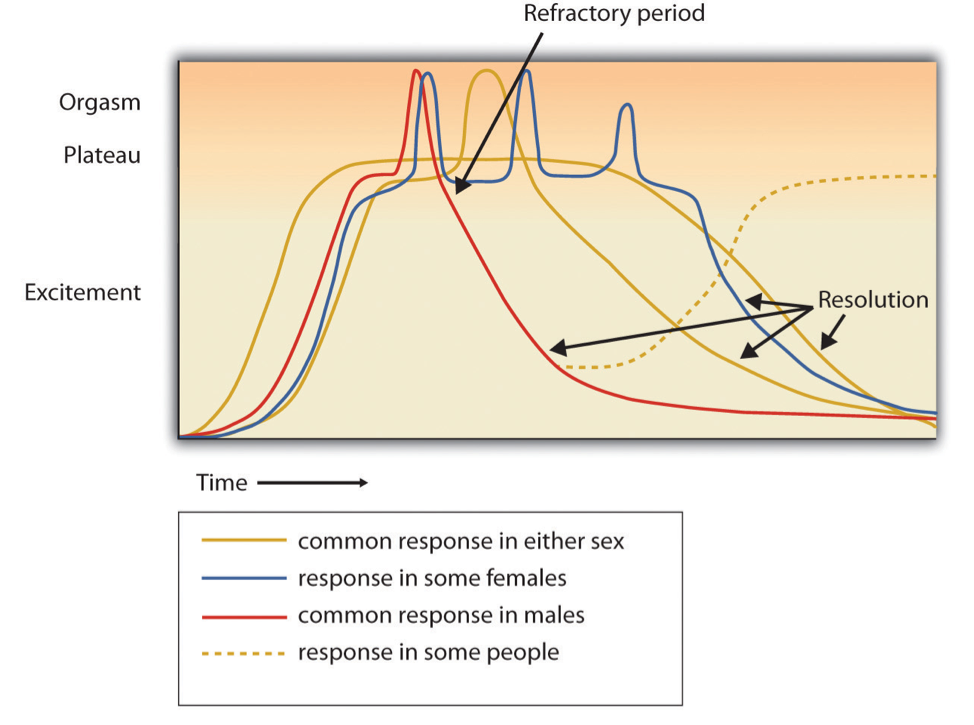

Models of sexual functioning can be considered culturally specific descriptions of the role and function of sexual activity relative to a particular time and place. Early models are said to date from Ancient Egyptian culture (Carroll, 2015) and have varied enormously across the centuries and between cultures. The modern Western approach to sexual functioning focusing on a scientific examination of sexuality began in the 19th Century in Western Europe becoming known as the academic and clinical discipline of sexology (Djajic-Horváth, 2015). This work concerns itself with the model of human sexual functioning that begin with Masters and Johnson’s (1966) linear, sequential model. The Masters and Johnson model, which was based on recording people’s sexual experiences either on their own or with a partner, divides sexual functioning into four phases: sexual excitement, plateau, orgasm and resolution. Each phase corresponds to changes in genital physiology, beginning with an excitement phase of general sympathetic arousal, myotonia (muscular rigidity after contraction) and increased blood flow to the genitalia, which may culminate in the sympathetically mediated spinal reflex of orgasm (Pfaus et al., 2016).

While Masters and Johnson’s model was ground-breaking and, importantly, based on empirical findings, it has been criticised for its focus on genital responses as the determinants of sexual function. It has also not necessarily been helpful to try to differentiate aspects of a physiologically continuous response using discrete verbal labels for specific phases (Rowland, 2006). Male and female genitalia are structurally similar and have common foetal origins (e.g. the penis and clitoris have physiologically similar tissue; testicles and ovaries have their origin in the same undifferentiated gonadal foetal tissue) and so can be expected to behave in physiologically similar ways. However, Masters and Johnson were able to differentiate between male and female sexual response according to the ability of females to have multiple orgasms whereas males require the resolution of a refractory period prior to having subsequent arousal and orgasm (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Four-Phase Sexual Response Model of Masters and Johnson (1966). Figure © https://sexinfoonline.com/the-sexual-response-cycle/

The Masters and Johnson model therefore assumed that, apart from that difference, male and female sexual responses were identical in overall form and sequence. This had the positive effect of dispelling the myth of the superior maturity of women’s so-called vaginal orgasm (i.e. an orgasm achieved by a woman during vaginal intercourse) over a more “immature” clitoral orgasm, as originally proposed by Freud (1905/1962). In fact, recent research suggests that female orgasms are much more complex and misunderstood phenomena than that simple distinction suggests. Pfaus et al. (2016) describe the “enormous potential” women have to experience orgasms from a diverse range of sensory inputs, including the external clitoral glans, an internal region that corresponds to the internal clitoral bulbs (known colloquially as the “G-spot”), the cervix, and stimulation of non-genital areas such as the nipples. The authors suggest that with experience and over the course of the lifespan, women have the potential to integrate sensory inputs with movements, body positions, autonomic arousal, cues from either partner or erotic context to induce pleasure and orgasm reliably during either masturbation or partnered sex.

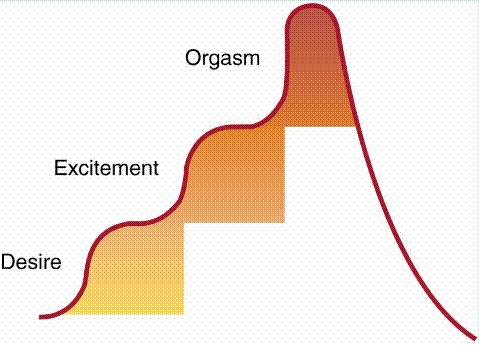

Kaplan’s (1979) three-phase model broke from Masters and Johnson’s solely physiological, genitally oriented model by incorporating the explicitly psychological construct of desire. Kaplan’s model consists of separate phases of desire, excitement and orgasm (the refractory period is not included) (Figure 5). Kaplan added the desire phase as a motivational construct in an attempt to differentiate between individuals with varying levels of sexual frequency and intensity, which the Masters and Johnson model was unable to accommodate. Desire is seen as a precondition for the physiological responses of excitement and orgasm.

Figure 5: Kaplan’s (1979) triphasic model of sexual response. Figure © http://core.ecu.edu/hhp/vailsmithk/HLTH2050/Readings/Kaplan.html

Kaplan’s triphasic model was regarded as being very useful in treatment settings as it allowed sexual dysfunctions seen in clinical practice to be differentiated in a meaningful way. It was incorporated into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) where the range of sexual dysfunctions seen in clinical practice were mapped on to stages of sexual function (Hawton, 1985). Specifically, people reported either diminished or heightened sexual desire or interest in sex (hypo or hyperactive desire); sexual arousal/excitement problems such as erectile dysfunction in men or insufficient vaginal lubrication in women), or problems with orgasm, which could be too rapid, delayed, or absent (anorgasmia). In addition, a separate category was added of problems that did not correspond simply to phases of sexual functioning but were more global in their impact on sexual functioning. These included sexual phobia (or aversion), genito-pelvic pain (such as vulvodynia), and vaginismus, an involuntary reflex muscular contraction that prevents penetration or makes any attempt at it extremely painful and uncomfortable (Hawton, 1985).

By incorporating a psychological element Kaplan’s model paved the way for the development of models of sexual functioning that are more contextual, that is, they are able to consider the setting in which sexual activity occurs and to differentiate more clearly between female and male sexual functioning. Reed’s Erotic Stimulus Pathway proposed four stages of sexual response termed seduction, sensations, surrender and reflection, which correspond to desire, excitement, orgasm and resolution. Whipple and Brash-McGreer (1997) proposed a circular model of female sexual response that suggested that pleasure and satisfaction from one sexual experience could lead to positive or negative expectations for future sexual experiences, thus increasing or diminishing desire (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Whipple and Brash-McGreer’s (1997) circular model of female sexual response. Figure © not known.

Basson’s (2001) non-linear model is also a circular model of female sexual response. It describes how physiological, psychological, relationship and cultural factors interact in complex ways. Basson stated that the precondition for sexual responsiveness in women is a state of sexual neutrality (with regard to desire) accompanied by a willingness to be sexually aroused (Figure 7). This view was expanded by Tiefer (2001) in her “New View of Women’s Sexual Problems” in which she states that in general women do not separate “desire” from “arousal”, care less about physical than subjective arousal, and that their sexual complaints frequently focus on “difficulties” that are absent from the DSM, such as problems related to socio-cultural, political or economic factors. The most recent edition of the DSM, DSM-5 has consciously moved away from a sole focus on medical issues and recognised the value of circular models.

In support of these contextual, circular models, there is evidence that women are more likely than men to interact in sexual behaviours even when they do not find them sexually arousing, which suggests that gender roles and sociocultural factors play an important part in women’s sexual functioning (Geer & Broussard, 1990). In addition, the evidence for increased levels of sexual plasticity in women relative to men (Baumeister, 2004), suggests that men’s and women’s’ sexual functioning are qualitatively distinct. However, men too experience social and peer-related pressures to conform to stereotypes of masculinity in their sexual functioning, which clinical experience suggests is exacerbated by a reliance on the stereotypical sexual scripts of much readily-available pornography to define appropriate sexual functioning and behaviour.

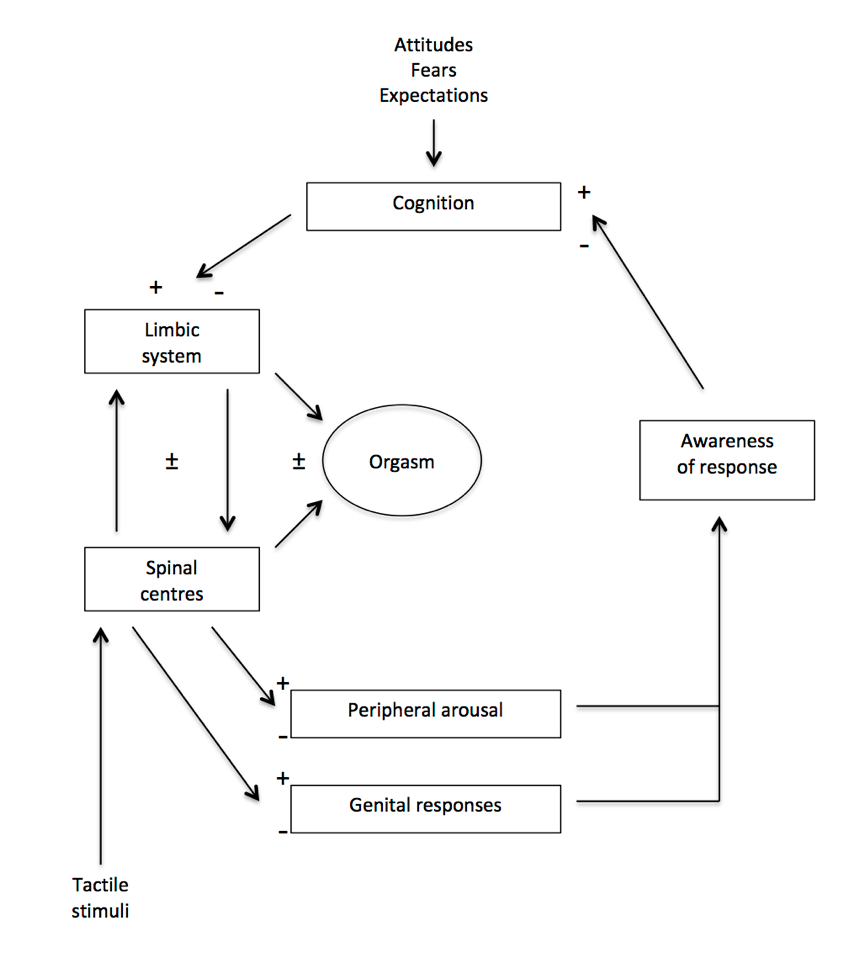

Bancroft (2009) combines biological and psychological mechanisms in the psychosomatic circle of sex (Figure 8). This model describes a whole body and mind experience in which there are significant links between a number of factors. These include: conscious and unconscious psychological processes; the role of the “emotional brain” (i.e. the limbic system); and the spinal cord and reflex centres within it. These latter processes control genital responses such as vasocongestion and other peripheral manifestations of sexual excitement, such as skin flushing, through the actions of both somatic and autonomic nerves. Cognitive processing of the awareness and perception of these peripheral and genital changes completes the circle whilst orgasm, which Bancroft states is still not well understood at a neurophysiological level, occupies a symbolically central position. Post orgasm resolution, including a male refractory period, affects various elements of the circle. Whilst the process leading to sexual response could start anywhere in the circle (for example in tactile stimulation to the periphery) it is the meaning ascribed to this stimulation that distinguishes certain forms of stimulation as sexual whereas others are not. At each juncture in the model there is either a plus, minus or plus/minus symbol that is fundamental to the workings of the model – the plus symbol represents excitatory mechanisms that are part of amplificatory feedback loops, whereas the minus represents inhibitory mechanisms that attenuate sexual responsiveness – this aspect of the model is elaborated in the Dual Control model.

The Dual Control Model is an explicitly biopsychosocial model that gives equal prominence to biological, psychological, social and cultural factors in sexual functioning (Figure 9) (Janssen & Bancroft, 2006). it also suggests that sexual excitation and inhibition are processes that are mediated through separate pathways. Janssen and Bancroft claim that psychological processes and genital responses depend on both the presence of a sexual stimulus, and the absence of factors that interfere with the activation of a response to the sexual stimulus. This results in a “sexual tipping point” that balances the net effect of sexual excitation and inhibition. It is the interplay between the physiological, biological, psychosocial, cultural and behavioural aspects of a situation that generate an individual’s level of sexual responsiveness at any given time and at any given point in the various phases of the sexual response cycle (Perelman, 2006). Conceptualising these two processes as independent suggests that inhibitory processes may differ between men and women. In men, the inhibition of a sexual response in the presence of an excitatory sexual stimulus could, for example, involve either a fear of performance failure (resulting in loss of esteem or dignity) or a fear of the consequences (e.g. a sexually transmitted infection).

Research is less well developed on the same processes in women, although preliminary data suggests that similar processes exist, with excitation processes being weaker than in men and inhibition effects greater, suggesting a greater role for women than for men of cultural and relationship factors such as loss of reputation, body image evaluation, and poor quality of relationship. Both pathways are adaptive: inhibition acts to promote safety in threatening circumstances, whereas excitatory processes allow people to take advantage of opportunities for sexual rewards (Bancroft, 2009).

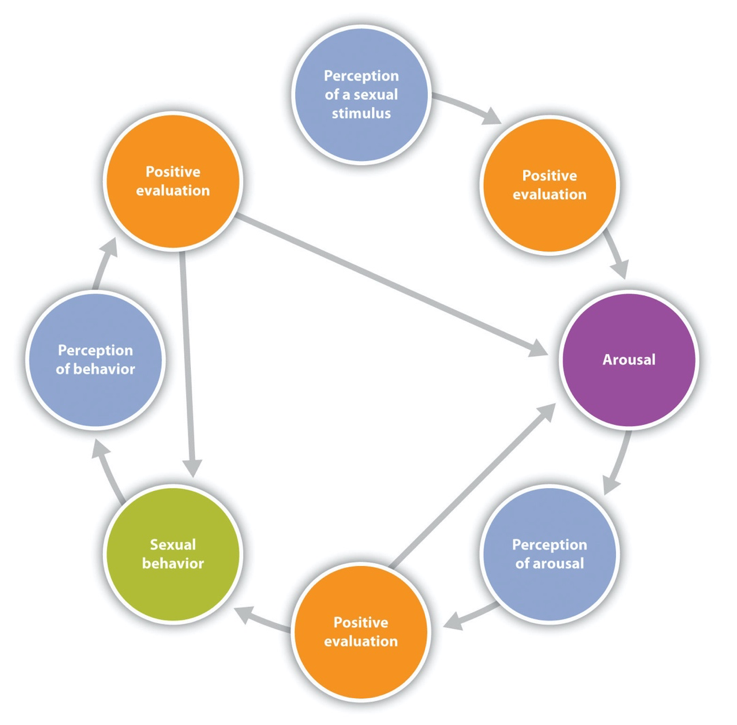

Walen and Roth’s (1987) model of sexual function is an explicitly psychological model based on the impact of evaluation of stimuli on arousal and excitability, starting with the appraisal of a perceived sexual stimulus (i.e. whether it is considered welcome/appropriate etc.) that determines whether there is a physical response, which in turn is appraised. In effect the model delineates a sequence of positive (excitatory) and negative (inhibitory) feedback loops where the perception of a sexual stimulus is appraised as welcome or unwelcome leading, if welcome, to arousal. When arousal is perceived that too is evaluated and if positive leads to sexual behaviour, which too is appraised, leading to increased arousal (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Walen and Roth (1987) model of sexual response (inhibitory negative evaluations not shown). Figure © not known.

In a similar vein Barlow’s (1986) model of sexual function and dysfunction (Figure 11) also focuses on appraisal of sexual stimuli and erotic cues but highlights the role of focused attention, which is a feature of anxiety disorders in particular, thus highlighting the role of anxiety in sexual dysfunction. It suggests that when situations are appraised as potentially dangerous, then anxiety causes the person to focus their perception on non-erotic cues. In particular, perceptions that are self-evaluative and which intensify negative emotion and decrease positive emotion are thought to have a powerful impact on desire and arousal. Worry and accompanying hypervigilance for cues for performance failure (e.g. perceiving one’s partner as sexually unresponsive) intensify the focus on self-evaluation rather than erotic cues and lead to dysfunctional sexual performance. An unsatisfactory sexual experience is appraised as being the consequence of personal inadequacy, which confirms the feared outcome and thus creates anxious anticipation of future sexual experiences (Wiegel et al., 2007). However, the role of anxiety in sexual function is not yet clear (McCabe et al, 2010) and so the model has to be treated with some caution.

Mosher (1980) proposed a model of sexual functioning that described sexual experience in terms of a person’s subjective depth of involvement, that is, how absorbed they become in the experience as well its meaning for them. Depth of involvement was described on a six-point scale from zero interest to ecstatic sexual role enactment. At zero involvement there is an avoidance or lack of interest in sex with no accompanying emotion or effort towards sex. At level 1, a casual enactment of the sexual role takes place and behaviour is detached or perfunctory. A person may imagine themselves in another role or have emotions that are inappropriate or angry to the situation. Level 2 is a routine sexual role enactment. Actions are mechanical and routine and there is a sense of going through the motions while feeling just enough to perform a sexual role in line with perceived expectations. At level 3 there is a more engrossed sexual role enactment where people throw themselves in to the sexual encounter more fully and take pleasure in it. At level 4 is an entranced sexual role enactment in which the self is fully engaged and merged with the sexual role and at level 5, there is the unusual and infrequent ecstatic sexual role enactment which has the quality of transcendence and can feel as though it is an intensely spiritual experience.